October 31, 2008

Jack London: Famous Author Chronicled Workers’ Struggles

(This article was first published in the November/December 2008 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Though best known as the author of widely acclaimed adventure stories such as The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and To Build a Fire, Jack London also chronicled the harsh lives many working people faced at the dawn of the 20th Century.

In a career that spanned only 16 years he wrote hundreds of short stories as well as non-fiction articles about current events and a wide range of topics for newspapers and magazines. Throughout his work, London espoused the theme that the “system” is stacked against working people, and he celebrated the rugged individuals who fought back.

Born to humble beginnings, London took on a wide range of the arduous jobs that were available to him as a young man. He hated the work and the poor pay, and saw life as a writer as a means of achieving his dreams.

Defined By His Work

Jack London was born in San Francisco in 1876 and grew up in Oakland, where he first went to work at age 10, peddling newspapers. He also loaded ice, set up pins in a bowling alley, and swept out saloons. After graduating from 8th grade, he was hired for 10 cents an hour to operate a soldering machine at a cannery.

London saved a few dollars and bought a “skiff,” a small boat he taught himself to sail. At age 15, secure in his navigational skills, he borrowed money for a single-mast sloop, and began a brief but thrilling career as an “oyster pirate.”

The trade was plied at night in the artificial mud flats next to Southern Pacific Railroad track beds. Entrepreneurs leased land to grow oysters from transplanted — and superior — Eastern stock. The public, which disliked the Southern Pacific and anything associated with it, liked cheap oysters.

London found it exciting and lucrative. “Every raid on an oyster bed was a felony. The penalty was state imprisonment …And what of that? The men in stripes worked a shorter day than I at my machine. And there was vastly more romance in being an oyster pirate or a convict than in being a wage slave.”

Sailor, Hobo, Orator

At age 17, London signed on to the crew of a seal-hunting ship bound for the Sea of Japan. After six months as a seaman, he returned to Oakland, and worked in a jute mill and at a street-railway power plant. He quit that job, shoveling coal, when he learned that he had been hired to replace two men, and that fellow employees had been threatened with dismissal if they told him.

“Repulsed” by work, he became a hobo. As a vagabond, “I saw the wheels of the social machine go around … men without trades were helpless cattle,” he wrote two decades later inJohn Barleycorn. He tramped back to Oakland, and decided to better himself.

London attended Oakland High School, doubling as the school janitor. “I was working to get away from work, and I buckled down to it with a grim realization of the paradox.”He dropped out of school, passed a rigorous entrance exam and briefly attended college, and developed a reputation as “The Boy Socialist of Oakland,” his literary output consisting largely of fiery letters to newspapers.

London attended Oakland High School, doubling as the school janitor. “I was working to get away from work, and I buckled down to it with a grim realization of the paradox.”He dropped out of school, passed a rigorous entrance exam and briefly attended college, and developed a reputation as “The Boy Socialist of Oakland,” his literary output consisting largely of fiery letters to newspapers.

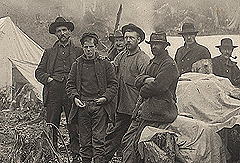

Then he heard about a gold strike, and in 1897, with the financial backing of his brother-in law, he headed for the Yukon.

As most first-time miners were to learn, the good claims had all been taken by the time the news of the gold-strike reached the “outside.” London and his partners did file a claim, however, and spent the winter nearby in a cabin built by earlier prospectors. To the future author’s luck, the location, Dawson City, was a major crossroads. During the Alaskan winter, there were frequent visitors with nothing to do but share their stories from the goldfields.

Suffering from scurvy and accepting that he would never luck into a fortune, London returned home. Now 22, he found that his father had died and that he was expected to support the remaining family. “I mowed lawns, trimmed hedges, took up carpets, beat them, and laid them again.” He pawned his watch and bicycle, and tried, without luck, to sell his writing. He was desperate.

Almost a Postal Worker

“I took the civil service examinations for mail carrier and passed first. But alas, there was no vacancy, and I must wait.”While he was waiting, a newspaper offered to pay him for a Klondike adventure story.

“And just then came the call from the post office. … The $65 I could earn regularly every month was a terrible temptation. I couldn’t decide what to do. And I’ll never be able to forgive the postmaster of Oakland.”

“I frankly told him the situation: It looked as if I might win out at writing. The chance was good, but not certain. Now, if he would pass me by and select the next man on the eligible list, and give me a call at the next vacancy…”

“Literally and literarily I was saved,” he recalled of his rejection, and “the cursed brutality” of the postmaster. The short tale of the Yukon netted him $40, the “first real money I ever received for a story.”

While some of his early published writings created a stir, they did not make London wealthy. And he always maintained that money was his primary motive for writing.

In 1899, Cloudesley Johns, the only employee of a small desert Post Office in Harold, CA, struck up a correspondence with London by sending him a fan letter. “It’s money I want,” London wrote to Johns early the next year, “or rather the things money will buy; and I can never possibly have too much.… More money means more life to me. The habit of spending money, ah God! I shall always be its victim. If cash comes with fame, come fame; if cash comes without fame, then come cash.”

The Ranch Years

In 1903, when The Call of the Wild was published to international acclaim, London made his first visit to Glen Ellen, a farming community about 50 miles north of San Francisco. In 1905, he bought a ranch, which he gradually expanded to 1,400 acres. This was what he and Charmian Kittredge, his second wife and “soul-mate,” would call home.

For the last decade of his life, London obsessed over the ranch, supervised the building of the Snark, which he hoped to sail around the world for seven years (the ill-fated venture ended after less than two), covered wars and boxing for magazines and newspapers, and travelled to New York and Los Angeles to work for authors’ rights. He developed a gradually increasing ambivalence towards socialism.

His office was in a shed on the ranch, or he would sit and work under a tree just outside. He wrote every morning, 1,000 words, no matter where he was, no matter what the topic, as long it meant financial reward. He drove himself hard, and was a soft touch for those who worked for him or came by his ranch for handouts.

In the summer of 1916, London resigned from the Socialist Party, “because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle.” That fall he died in his bed, his years of hard living taking their toll on his kidneys and his heart.

What Is The Scab ?

The Scab, a short essay that is said to describe workers who refuse to join their unions, has achieved icon status in labor circles and is frequently attributed to Jack London, but the passage does not appear in any of his published work. In the book The War of the Classes, London included a speech he gave in 1903 that made numerous references to scabs, but the speech featured none of the colorful language in The Scab. London scholars agree that the tone and colloquialisms are more suited to characters in his novels than to the writer himself.