February 28, 2015

From ‘Collective Begging’ Collective Bargaining

March 2015 marks the 45th anniversary of the Great Postal Strike of 1970. The courage and solidarity shown by thousands of union members during the wildcat job action resulted in vastly improved wages and benefits.

March 12, 1970

The stage was set: Postal workers had suffered decades of long hours, substandard pay, meager benefits, and deplorable working conditions, and their only recourse had been to beg for better treatment.

Most postal workers belonged to one of seven craft unions recognized by the federal government, but they were denied a key right of private-sector unions: to bargain collectively over compensation. Although President Kennedy issued an executive order in 1961 that recognized government-employee unions, postal and other federal workers were barred from striking and could seek wage and benefit increases only by petitioning Congress — a course that usually met with inaction.

The sporadic raises that postal workers received never seemed to amount to much, particularly in high-cost urban areas. In March 1970, full-time employees were paid approximately $6,200 to start, and workers with 21 years of service averaged only $8,440, which was barely enough to make ends meet: Many full-time postal workers qualified for food stamps.

Meanwhile, a presidential commission had concluded in 1968 that postal workers deserved the same collective bargaining rights that private-sector workers enjoy under the National Labor Relations Act.

Even though Congress failed to act on the commission’s recommendation, postal workers two years later were still optimistic that sizable pay raises were forthcoming.

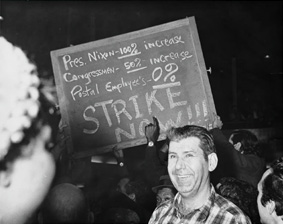

On March 12, 1970, Congress finally did act: It gave itself a whopping 41 percent pay hike, and offered postal workers only a 5.4 percent raise. In postal facilities across the country, outrage spread like wildfire.

March 18, 1970

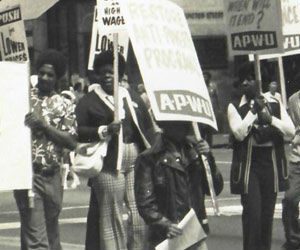

Five days later, irate letter carriers of New York City’s Branch 36 voted to strike the next morning, March 18. Clerks and other members of the Manhattan-Bronx Postal Union (MBPU), led by their president, Moe Biller, refused to cross the picket line. The strike was on!

The wildcat job action quickly gained support from postal workers across the country — much to the consternation of postal executives, the Nixon administration officials and national union leaders.

But that didn’t matter to postal workers who were tired of being taken for granted. “We’re used to hard times,” a striker told Time.

The MBPU voted to officially join the strike on Saturday, March 21. Many other locals endorsed the strike that day and the next, essentially shutting down mail service in 30 major cities and many small towns. By the following Tuesday, 200,000 postal workers had walked off the job, with many calling in sick. The strike had spread to 499 offices in 13 states: New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Colorado, Nevada, and California.

Mail destined for New York and other major cities in these states “began piling up by the ton,” Time reported. “After just a few days of stoppage, and with parts of the system still operating, the effects of the shutdown appeared to be little short of devastating” as the movement of letters, business mail, financial transactions, and government documents ground to a halt.

Mail destined for New York and other major cities in these states “began piling up by the ton,” Time reported. “After just a few days of stoppage, and with parts of the system still operating, the effects of the shutdown appeared to be little short of devastating” as the movement of letters, business mail, financial transactions, and government documents ground to a halt.

The strike was front-page news across the country, and brought a great deal of attention to the plight of postal workers. But the leaders of the seven national unions, fearing a backlash from the public, had met with Postmaster General Winton Blount and secured a pledge that “if a substantial number of employees would return to work by Monday, March 23, negotiations would begin” over pay and other improvements.

The union leaders urged the strikers to accept Blount’s offer and return to work, but many thousands refused and demanded that negotiations commence immediately. In response, President Nixon decried the illegal job action and vowed to break the postal workers, telling the nation on March 23, “We have the means to deliver the mail.”

March 24-25, 1970

Nixon sent more than 23,000 Army, Marine and Air Force personnel to New York City postal facilities with orders to transport, sort, and deliver the mail. To the surprise of very few postal workers, without proper training, the troops proved woefully inadequate to the task.

Within hours, while courts were serving injunctions and imposing fines against union leaders, the postmaster general defused the situation by arbitrarily announcing that enough workers had returned to the job and negotiations would begin immediately.

Bargaining began and ended quickly: In a preliminary agreement reached the first day of talks, the Post Office Department offered a 12 percent pay increase, retroactive to October 1969; a decrease from 21 to eight in the number of years required for a worker to reach the top step in the wage scale; real collective bargaining rights, and amnesty for all strikers.

Striking and “sick” postal workers across the country returned to the job March 25.

The final agreement, announced a month later, however, fell short of the PMG’s promises; to achieve some of them, Congress would have to fund the pay increase and change the law on bargaining.

Congress quickly approved a 6 percent wage increase, retroactive to the previous December, and on Aug. 12, 1970, President Nixon signed into law the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970 (PRA), which gave postal workers an additional 8 percent raise and shortened the time it took to reach top pay. In granting postal workers the right to bargain collectively over wages, benefits, and working conditions, the PRA also instituted a binding arbitration process for resolving contract disputes. (Strikes remain illegal to this day.)

The PRA also abolished the Post Office Department and established the U.S. Postal Service as an independent agency funded only by postage sales and services.

Birth of the APWU

In January 1971, the five-month-old USPS participated in the first collective bargaining session with seven postal unions, including five that would merge into the APWU on July 1, 1971.

On July 20, 1971, a two-year contract with the Postal Service was signed by the APWU unions, along with the National Association of Letter Carriers, the National Rural Letter Carriers Association, and the National Postal Mail Handlers Union. In the first agreement, a starting postal worker’s salary was set at $8,488 — more than a 21-year veteran of the Post Office Department had been getting when the job action began 16 months earlier.

Subsequent contracts have helped postal workers claim a piece of the American Dream: owning homes, supporting families and communities, and enjoying job security, decent healthcare and retirement benefits.

“The most important achievement of the strike was winning the right to bargain collectively,” recalls APWU President William Burrus. “By standing together we had become a real union.”

In the months and years after the job action, many strikers went on to become leaders of union. Moe Biller was elected president of the national APWU in 1980, a position he held until 2001. In 2010, old-timers who took part in the strike can look back with pride at what the strike accomplished — for millions of workers who have since reaped the benefits, and for what remains the world’s largest and most efficient postal system.

For more information about the job action, visit the APWU History pages at www.apwu.org.

“The Strike that Couldn’t Happen”

Click here to watch a 16-minute video about the Great Postal Strike of 1970.