December 31, 2002

The Alliance That Began With the Brotherhood

(This article was first published in the January/February 2003 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

As the civil war divided the nation figuratively, transcontinental rail travel brought it together literally. The nation’s railroad system also brought together for the first time Black workers and the labor movement. From that alliance, several decades later, A. Philip Randolph would emerge as a major historical figure not just in labor, but in civil rights.

When George Pullman began to capitalize on the growth in passenger rail travel in the late 1860s, he had no idea that he was providing fertile ground for the Black labor movement. Pullman, who manufactured luxury rail cars, was concerned more about his customers than about his workers, whether in the factory or in the rolling “sleepers” hauled by the railroads.

Manufacturing was easy compared to serving passengers. At first, Pullman tried to use railroad employees to run his “hotel on wheels.” Soon, however, he turned to a largely untapped labor force, one in need of employment and willing to spend long days performing “servants’” duties. Sixty years after it had begun to corner the market in sleeper cars, the Pullman Company was America’s largest private employer of Black labor. And it was the service provided by that labor force that was the single most important selling point for the Pullman Company.

The Pullman Porter’s Status

In early 20th-Century Black America, a Pullman porter was a man of great social importance. He wore a uniform rather than a laborer’s clothes. He was sophisticated, comfortable in urban settings. His music was the “jazz of the big city” rather than “backwater blues.”

Just one generation removed from slavery, the Pullman porters had status in their community and were paid relatively well. To African-Americans, the job of a Pullman porter was, quite simply, the best job available. And by 1925, when railroad travel was nearing its peak, there were more than 20,000 Blacks working as Pullman porters, making it the largest category of Black labor in the United States and Canada.

Also in the mid-1920s, a Department of Labor report declared that the average American family needed $2,000 in annual salary to maintain “a decent living.” The Pullman porter made about a third of that in base salary, about half of which went for expenses — porters had to spend their own money on meals, stopover lodging, uniforms, and even the shoe polish they needed to make more in tips, which could easily double a porter’s income.

Asa Philip Randolph’s association with Pullman porters had its genesis in his arrival in New York’s Harlem in 1911, at age 22. He had excelled at Cookman Institute, the first high school for African Americans in Florida, and wanted to attend college, which his family could not afford.

After a few years in menial jobs, he went north to seek his fortune, with a secret desire to become an actor. He enrolled at City College where, to disguise his theatrical ambitions, he studied economics. His studies led him to the Socialist Party and it was through his politics that he became known as an orator. He also launched The Messenger, a radical Harlem-based magazine, in 1917.

Pullman porters, meanwhile, had made three or four futile attempts at organizing, hampered each time by large measures of anti-labor sentiment and racial discrimination. New York-based Pullman employees in 1925 decided to try again and contacted Randolph because they considered him a good speaker and knew him as a tireless fighter for civil rights. They also thought it important that their leader not be a porter — and thus not subject to Pullman Company retaliation.

Birth of the Brotherhood

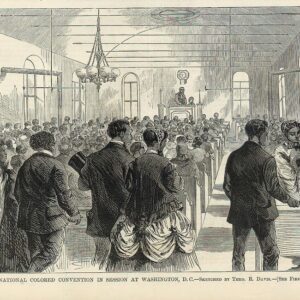

After a number of secret meetings, the organization of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was announced at Harlem’s Elks Hall on Aug. 25, 1925.

The Pullman Company was the porters’ only employer. It responded to the BSCP’s formation with threats and firings, and subsidized efforts to paint the Brotherhood “red” in the African-American press. Randolph was branded an “outside agitator,” a Bolshevik, and a hustler out for a fast buck. At work, Pullman threatened union sympathizers with tougher assignments, fewer assignments, or no work at all.

In 1928, with membership in the union at more than 50 percent, Randolph called for a strike. On the advice of the American Federation of Labor, however, the job action was called off.

By 1935, the Brotherhood had survived both Pullman management and much of a national Depression. That year it won an election supervised by the National Mediation Board and was granted an international charter by the AFL. It took two more years to negotiate the first Pullman Company contract, the first ever between an American business and an African-American union.

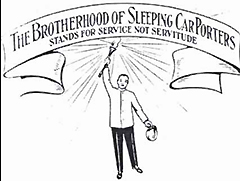

After the BSCP: The National Arena

The porters gained pay increases, shorter work weeks, a reduction in the amount of miles they had to travel, and widespread respect. They were working to and living up to their motto, which stated that the Brotherhood “Stands for service, not servitude.” Randolph maintained his union leadership and became a national spokesperson for African-American rights, with his focus always on jobs.

In 1941, with the war effort heating up, Randolph spoke out against the use of Black taxpayer money going to industries that refused to hire Black workers. He planned a massive national protest in Washington, and found widespread support among Black churches and other groups eager to bring attention to social and economic inequities. Before the march planned for July 4 could take place, however, President Roosevelt signed an executive order banning discrimination in government hiring practices and among the defense industries holding government contracts. A Fair Employment Practices Committee was set up to implement the order.

In 1947, Randolph again pressured a president over civil rights, again over work. When President Truman called for a peacetime draft, he failed to ban segregation in the armed forces. Randolph mobilized Blacks to refuse to register and to refuse to serve if called, and a mass protest again was planned for the nation’s capital. On July 26, 1948, Truman issued an executive order barring discrimination in the military.

In 1963, there finally was a “March on Washington,” during which more than a quarter-million gathered under the slogan of “Jobs and Freedom.” Randolph was one of the main organizers and in effect introduced Martin Luther King Jr. to the national stage during that event, passing on the civil rights leadership in a very public way.

King himself always insisted that the labor movement and the civil rights movement were one and the same. It was his support of a job action — a sanitation-workers’ strike — that brought him to Memphis, where he was felled by an assassin’s bullet in 1968.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters went the way of the passenger railroad, its few remaining members absorbed by what is now the Transportation-Communications Union in 1978. Randolph, who had retired from public life when he turned 80 a decade earlier, died in 1979.