August 31, 2015

‘Big Bill’ Haywood: The ‘Wobbly’ Giant

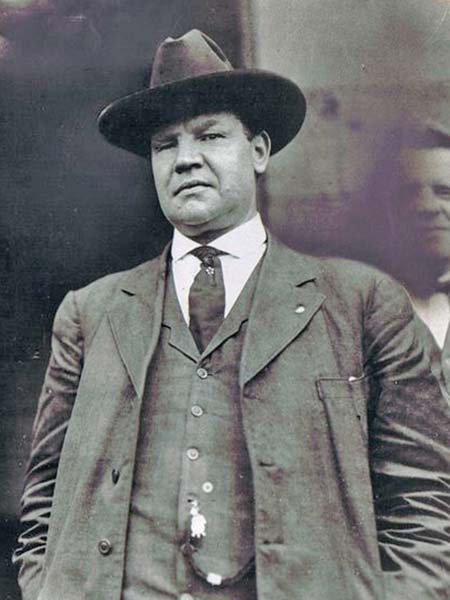

“Big Bill” Haywood was a big man with a big heart and a big dream – to build one big union for workers from every industry. He could break a man’s jaw with a single blow, but he wept openly when a poem moved him.

“Big Bill” was born William Dudley Haywood on Feb. 4, 1869, in Salt Lake City. He learned hard lessons early in life. His father, a Pony Express rider, died when he was 3; he witnessed a fatal gun duel between classmates at age 7, and at age 9, he blinded himself in one eye in a slingshot accident.

But it was an incident he observed at age 15 that changed Haywood forever: He saw a black man lynched. Shaken to the core, he resolved to fight oppression.

Turning Point

That same year, Haywood started working in a Nevada mine. The heavy labor left him so exhausted that at the end of the day he could barely walk back to the company-owned barracks where he slept.

But when Haywood learned from a member of the Knights of Labor about the empowerment unions gave workers, he was revitalized. He soon found inspiration in the 1894 American Railway Union strike. “The big thing was they could stop the trains,” he observed.

Haywood was on fire with unionism by the time he got a job at the Blaine Mine in Silver City, ID, in 1896, but soon after he started, his right hand was crushed, forcing him to give up mining.

As luck would have it, at about the same time, Ed Boyce, president of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), came to town on an organizing tour. Haywood got involved and quickly rose through the ranks. He was elected WFM secretary-treasurer, and moved its headquarters to Denver, where he led the fight for the eight-hour day and organized massive strikes.

His most famous battle was at Cripple Creek, CO, in 1903, where he led a strike that lasted 15 tumultuous months. It was like a war.

Mine owners paid soldiers to infiltrate the town, seize police headquarters, and illegally detain anyone who sympathized with the workers. Strikers, reporters, lawyers and members of other unions were held in a bullpen for weeks, surrounded by barbed wire. Mine bosses paid vigilantes to plant bombs, then blamed the explosions on strikers.

“The only answer I could find in my own mind was to organize, to multiply our strength,” Haywood wrote. “As long as we were scattered and disjointed we could be victimized.”

The workers stood their ground, and on Dec. 1, 1904, the bosses gave the strikers what they had been asking for all along: $3 minimum for an eight-hour day.

One Big Union – On Rails

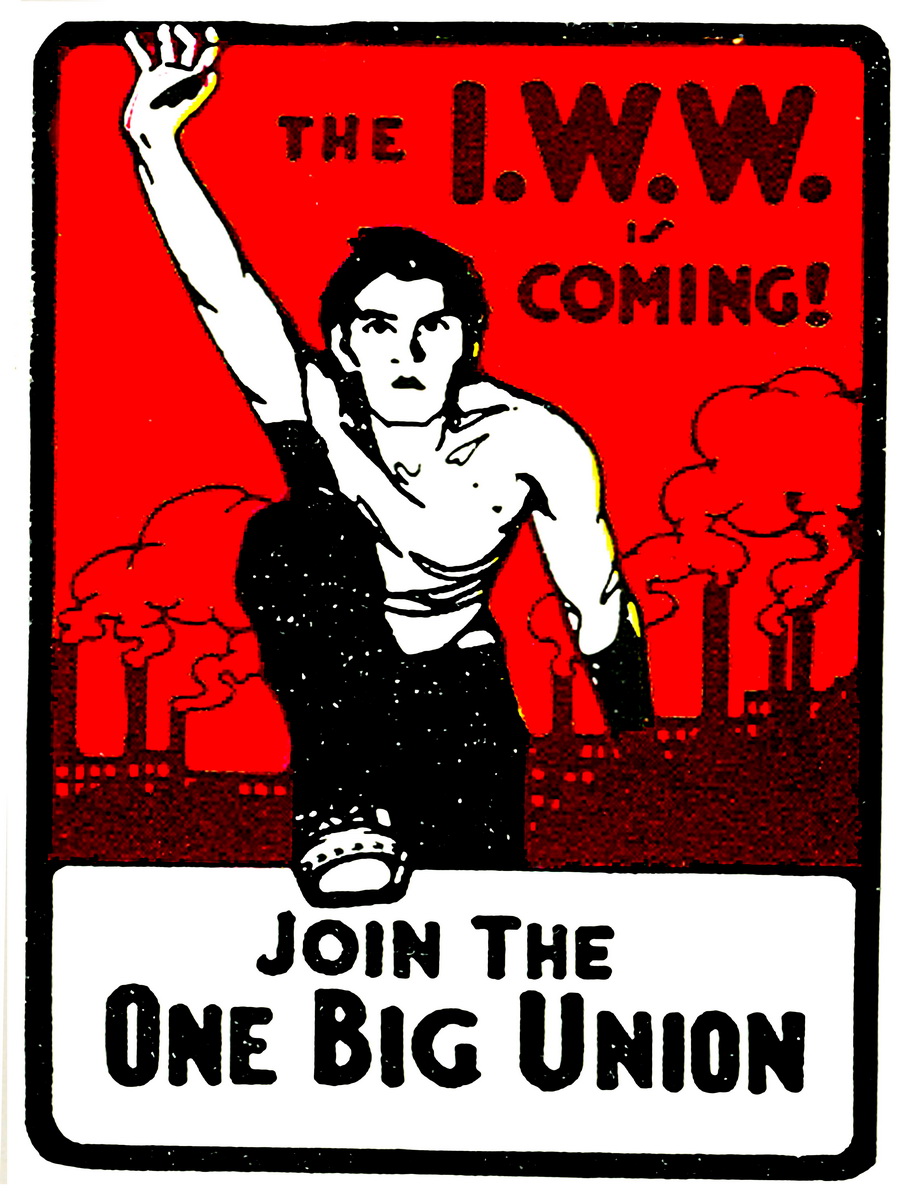

Hoping to expand unionism in the undeveloped West, Haywood, Eugene V. Debs, Lucy Parsons, “Mother” Jones and other labor leaders organized the Industrial Workers of the World at a meeting in Chicago on June 27, 1905.

It was “one big union,” for workers nationwide in all industries, crafts and trades. This was in sharp contrast to the AFL, which was a federation of exclusive, craft-based organizations of skilled workers.

Known as “Wobblies,” IWW members included workers from all walks of life, regardless of skill, sex or race – and Haywood was their most beloved leader.

“The miners saw themselves in him and they felt that if they could only make speeches, they would say what he said, the way he said it. They believed him fearless and incorruptible and if he was smart, well, he wasn’t fancy,” wrote Richard O. Boyer in Labor’s Untold Story.

Wobblies were radicals who believed in “direct action” to solve workers’ problems. They yearned for a “general strike” that would eradicate bosses.

They were constantly on the go, moving from state to state, organizing with songs and stories. One thousand strong, Wobblies would pour off freight trains at strike sites, singing rebellious songs. The 150,000 Wobblies influenced millions.

Assassination Trial, Witch Hunt

Mine owners were eager to silence the Wobblies, so they hatched a scheme to frame Haywood and his allies for allegedly assassinating the former governor of Idaho.

On Dec. 30, 1905, Harry Orchard, an informer working for the mine owners, made a bomb and planted it on the property of former Gov. Frank Steunenberg, killing him as he walked through his gate. Orchard then “confessed” that Haywood and his friends paid him $250 to do the deed.

Haywood was arrested, along with Charles Moyer, president of the WFM, and George Pettibone, a miner. Orchard’s testimony was so clearly false, that, despite intense pressure from “the powers that be” throughout the 17-month trial – where he was defended by Clarence Darrow – Haywood was acquitted.

Between 1909 and 1912, as their movement grew, thousands of Wobblies gathered in cities across the country. Leaders would stand on soap boxes asking workers to join the IWW and were often jailed or beaten by police acting at the behest of bosses.

Undeterred, when one soapboxer was arrested, another would take his or her place. Taxpayers soon complained that they were feeding armies of jailed Wobblies!

The IWW’s biggest victory was the two-month Textile Strike of 1912 in Lawrence, MA, known as the strike for “Bread and Roses.” Not only did the workers – who were mostly women – win better pay, the strike marked the first major labor protest where workers overcame ethnic differences. It also set the stage for limits on child labor and progress over subsistence-only wages, workplace safety, and the right to organize.

But in the run-up to World War I, the government had its own agenda: a witch hunt against any leftist or radical, including Wobblies.

Citing the newly-passed Espionage Act of 1917, the federal government raided IWW offices across the country. Since the law deemed any behavior that interfered with the war effort criminal – including union organizing – Haywood and 100 others were arrested. Haywood’s trial dragged on for five months and exhausted much of the IWW’s resources.

In 1918, Haywood and other leaders were convicted. Haywood was sentenced to 20 years in jail and fined $30,000.

After a year in jail, he jumped bond while out on appeal and sought refuge in Moscow. He died there on May 18, 1928.

Textile Strike in 1912. Seen here are strikers, who

are mostly female.

IWW Legacy

Despite the IWW’s unbridled enthusiasm, the organization was beset by internal disputes and its membership declined dramatically after World War I to about 15,000 in 1922.

Wobblies believed in permanent rebellion – and refused to engage in any negotiations with the bosses – so the IWW was unable to establish a baseline from which workers could advance their cause.

And many leaders believed that as impassioned members joined the IWW, they left the mainstream unions without their most aggressive and spirited fighters, weakening the labor movement as a whole.

Although the IWW lost its power, the spirited culture of rebellion that Haywood created will never die.