April 30, 2010

Bloody Showdown on the Road to Union Rights

“Load sixteen tons, what do you get? Another day older and deeper in debt. Saint Peter, don’t you call me, ‘cause I can’t go; I owe my soul to the company store.” – Coal miner and folk singer George S. Davis, 1904 – 1992

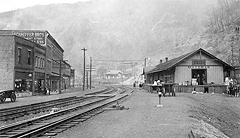

The mines of Appalachia were no place for the timid during the “coal wars” of the early 20th century. Following World War I, coal companies exploited workers, who were forced to endure miserable, dangerous job conditions. Wielding dynamite, picks, and shovels, miners removed coal from cramped and dirty underground seams amid the constant risk of fires, cave-ins, and other life-threatening hazards.

Hard Times

By 1920, rail, coal and timber companies had seized control of the richest lands in West Virginia and placed an economic stranglehold on families that had settled in the area generations before. The industrial barons who ruled the coal companies thrived on cheap labor — and they aimed to keep it that way.

A strike by the United Mine Workers (UMW) in 1919-1920 resulted in a 27 percent wage increase for coalminers in many parts of the nation, but miners in most of West Virginia, who remained unorganized, did not reap any benefits.

News of the UMW gains energized miners in Mingo County who wanted to unionize, especially in Matewan, a rough-and-tumble town tucked along the Tug River Valley on the Kentucky border, where the legendary Hatfield-McCoy feud had taken place decades before. Most miners in the valley worked for the Stone Mountain Coal Company. They lived with their families in company- owned housing and were paid in “scrip” that could be redeemed only at the company store. They had virtually no other choice of employment, and often lacked the hard currency to pay for transportation to another state.

When the company dropped wages to 90 cents per ton of coal and raised the price of food and supplies, many workers started “talking union” in earnest. In the spring of 1920, more than 3,000 Tug River Valley miners signed union cards. Matewan was soon to become the epicenter of a historic labor-management confrontation.

The Bosses Respond

As union support grew, Stone Mountain Coal fired every worker their spies could identify as pro-union.

The company also sent in gun-wielding private “detectives,” led by Albert Felts of the notorious Baldwin-Felts agency, to intimidate workers. “Felts had been one of the chief gunmen used by the coal operators in the Ludlow, CO massacre in 1914,” the UMW Web site notes, “in which 20 persons were killed, including 12 women and children who were burned alive in their tents.”

May 19, 1920

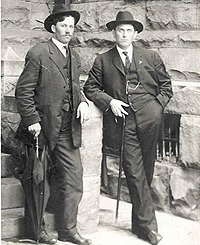

Tensions exploded when 13 additional Baldwin- Felts agents arrived in Matewan on May 19 to evict union supporters from company-owned land. Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield, who supported the miners, warned the agents that they lacked the proper documents to carry out evictions within town limits. Without the proper writs, he would arrest them, he said.

The agents defiantly vowed to carry out evictions in town the next day, then proceeded to evict six families from a camp on the outskirts of town, strewing their belongings along a muddy roadside.

Later that day, Chief Hatfield, accompanied by Mayor C.C. Testerman, confronted the heavily-armed Baldwin-Felts gang on the railroad tracks in front of the town’s post office, informing them that he had a warrant for their arrest. In turn, company “detective” Felts produced a warrant for Hatfield’s arrest, which Testerman determined was a fake.

As the two parties faced off, the Baldwin-Felts agents were unaware that they had been surrounded by armed miners who had been deputized by Hatfield.

The first shot, which Hatfield and several witnesses claimed was fired by Felts, struck Mayor Testerman in the abdomen: The battle was on. Hatfield shot Felts and several others amid a hail of gunfire that lasted several minutes.

The gunfight left seven Stone Mountain agents dead, including Felts and his brother, Lee. Testerman and two other townspeople were also killed. Hatfield was not hit. Several of the company gunmen fled the scene by swimming across the Tug River to Kentucky.

The Aftermath

News of the bloody confrontation galvanized the union movement. Within a month, 90 percent of Stone Mountain Coal’s workers had joined the UMW. In early July, they called a strike, and coal shipments from the Tug River Valley came to a halt. Hatfield, along with 22 others, was charged with murdering Albert Felts, but charges against 19 of the men were dropped. Hatfield and two others were acquitted.

The battle made Hatfield a hero for miners throughout the nation. However, 15 months later, Hatfield was arrested on false charges that he had shot up the nearby town of Mohawk more than a year earlier. He was taken from Matewan to McDowell County, which was a stronghold of anti-UMW coal operators. Upon their arrival on Aug. 1, 1921,Hatfield and his deputy, Ed Chambers, were assassinated on the courthouse steps by Baldwin-Felts agents.

No charges were ever brought against the murderers. The impact of the double murder was widespread: Thousands marched in the funeral processions for Hatfield and Chambers. Less than a month later, miners from across the state gathered at the state capitol in Charleston and began a march to Logan County, a coal operators’ stronghold. Ten thousand miners joined the group along the way, in what became the largest armed insurrection in the nation since the Civil War. The uprising, which culminated in the “Battle of Blair Mountain” in late 1921, will be the subject of a future “Look Back” article.

The West Virginia coal battles and other widespread union struggles in the early 20th century helped build support for the National Labor Relations Act of 1935,which has since protected workers’ rights to organize and bargain collectively. As the historian David A. Corbin stated, “The time has come to see Matewan in perspective, the way we do Lexington and Gettysburg — not just as an isolated incident of the tragic spilling of blood, but as a symbolic moment in a larger, broader and continuing historical struggle — in the words of Mingo county miner J.B. Wiggins, the “struggle for freedom and liberty.”