August 31, 2015

A Century After His Execution, Labor’s Legendary Troubadour Lives On

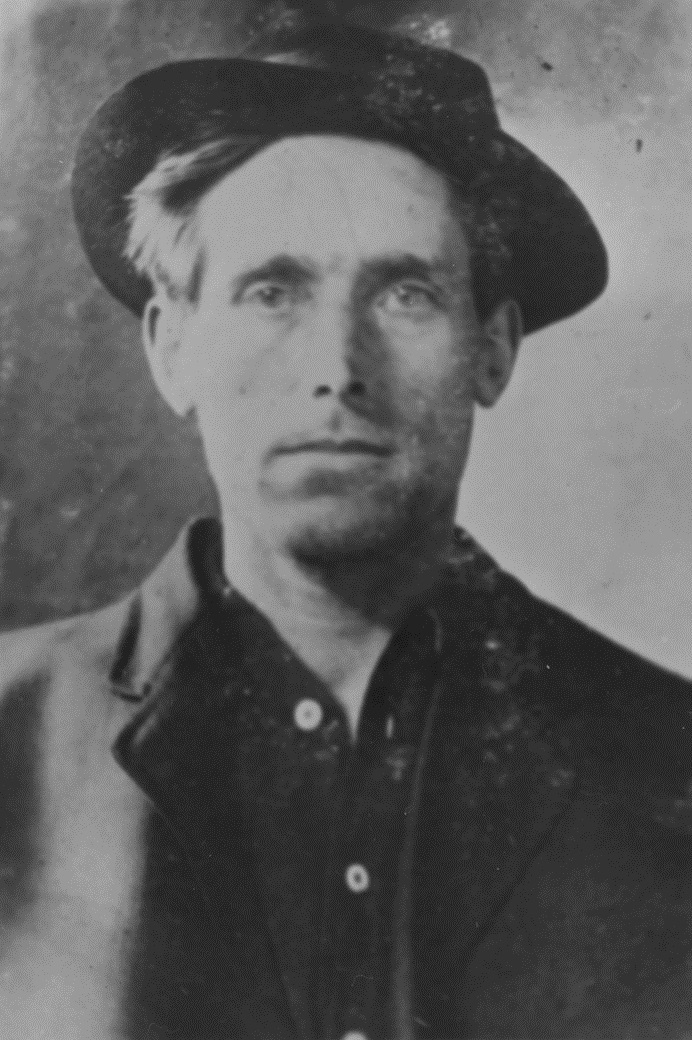

One hundred years have passed since a firing squad at the Utah State Penitentiary executed Joe Hill at sunrise on Nov. 19, 1915. The renowned labor organizer had been framed on a murder charge.

But a century after his death, the legend of “Joe Hill” is very much alive. In fact, activists across the country have been celebrating his life all year, with concerts and events that will culminate on Nov. 19.

In Salt Lake City, there will be an all-day festival, “Don’t Mourn, Organize!” on Saturday, Sept. 5, featuring performances by Judy Collins, Anne Feeney, Mark Ross, David Rovicks, Joe Jencks and Mischief Brew. It will take place in Sugar House Park, the site of the former prison where Hill was killed.

On Nov. 19, a candlelight vigil will be held at dawn at his execution site. Concerts will also be performed in Hill’s honor in Salt Lake City, Denver, and as far away as Berlin, Germany. On Nov. 22, a re-enactment of his funeral will take place in Chicago, complete with a casket, brass band and performers from around the world.

Who Was Joe Hill?

Joe Hill was born Joel Emmanuel Haaglund in Sweden. His father and two of his seven siblings had died by the time he was 8, and by age 9 he was working in a rope factory. At age 12, he moved to Stockholm to be treated for tuberculosis and picked up his only formal education, at a YMCA. There he learned to speak English and developed his talent for music and writing.

In 1902, at age 22, Haaglund immigrated to America to find a better life. He arrived penniless at Ellis Island, and after a stint cleaning bar spittoons, he left New York and began working as an itinerant laborer.

In his early life on the road, Haaglund worked as a miner, a fruit picker, and a logger. By 1910, he was going by the name Joseph Hillstrom.

‘One Big Union’

The 30-year old Hillstrom had grown increasingly disgusted with the corrupt system that held poor families captive to low-paying jobs in service of the wealthy. While working on the docks near Los Angeles that year, he joined the International Workers of the World (IWW), which welcomed women and minorities into its ranks and aimed to unite all workers in “One Big Union.”

The unchecked greed and exploitation of the so-called Gilded Age was crushing the dreams of most working people and the IWW rapidly grew in strength. Hillstrom became an organizer and adopted Joe Hill as a pen name, writing letters and songs that bolstered the spirits of striking workers.

Hill’s words and music were an inspiration to labor activists, and he was reported to be on the front lines of virtually every IWW job action during the organization’s heyday. Whatever his whereabouts, Hill was a daring troubadour at a time when bosses hired scabs, thugs, and crooked cops in the violent repression of union activity.

Between 1911 and 1913, he wrote dozens of songs that embodied the IWW’s message, including “The Preacher and the Slave” (1911), in which he coined the term “pie in the sky;” “Casey Jones – The Union Scab,” (1912),which was inspired by the strike of 40,000 railway shopmen, and “There is Power in a Union” (1913).

Framed in Utah

By 1913, when Hill’s union activities left him unable to find work in California, he hit the road again and ended up in Utah, a state that was extremely hostile to unions.

On Jan.10, 1914, a former policeman, J.B. Morrison, was shot dead in a gunfight with two assailants in his Salt Lake City grocery store. On that same evening, Hill visited a doctor for treatment of a bullet wound, the result, he said, of a quarrel over a woman.

Though Hill had never met Morrison, who long had feared a revenge attack from people he had arrested, Hill became a scapegoat for the murder. None of Hill’s blood – or the bullet that passed through his chest – was found at the scene. Four other men had been treated for bullet wounds in the area that evening, and forensic evidence supported Hill’s claim that he had been shot not during a gun battle, but while holding his hands over his head.

Hill could not afford his own lawyers and believed that his state-appointed attorneys were acting in collusion with his prosecutors. Yet for reasons unknown, he declined to testify in his own defense.

The controversial trial that condemned Hill to death rallied unionists and others around the world to petition Utah Gov. William Spry to release Hill or grant him a new trial. Hundreds of thousands of union members from Europe to Australia wrote letters to Spry, as did President Woodrow Wilson, the Swedish ambassador, the daughter of a prominent Mormon Church leader, and Helen Keller.

But Spry – who had promised to rid the state of “IWW agitators, or whatever they call themselves” – refused to release Hill and told the president and the Swedish government he would grant a new trial only if they could produce new evidence of Hill’s innocence.

In the 22 months between his arrest and execution, Hill wrote many letters, poems and songs, including such well-known lines as: “Workers of the world, awaken! Break your chains. Demand your rights. All the wealth you make is taken, by exploiting parasites… For united we are standing, but divided we will fall. Let this be our understanding: ‘All for one and one for all.’”

Photo credit: Special Collections, J. Willard Marriot Library, University of Utah

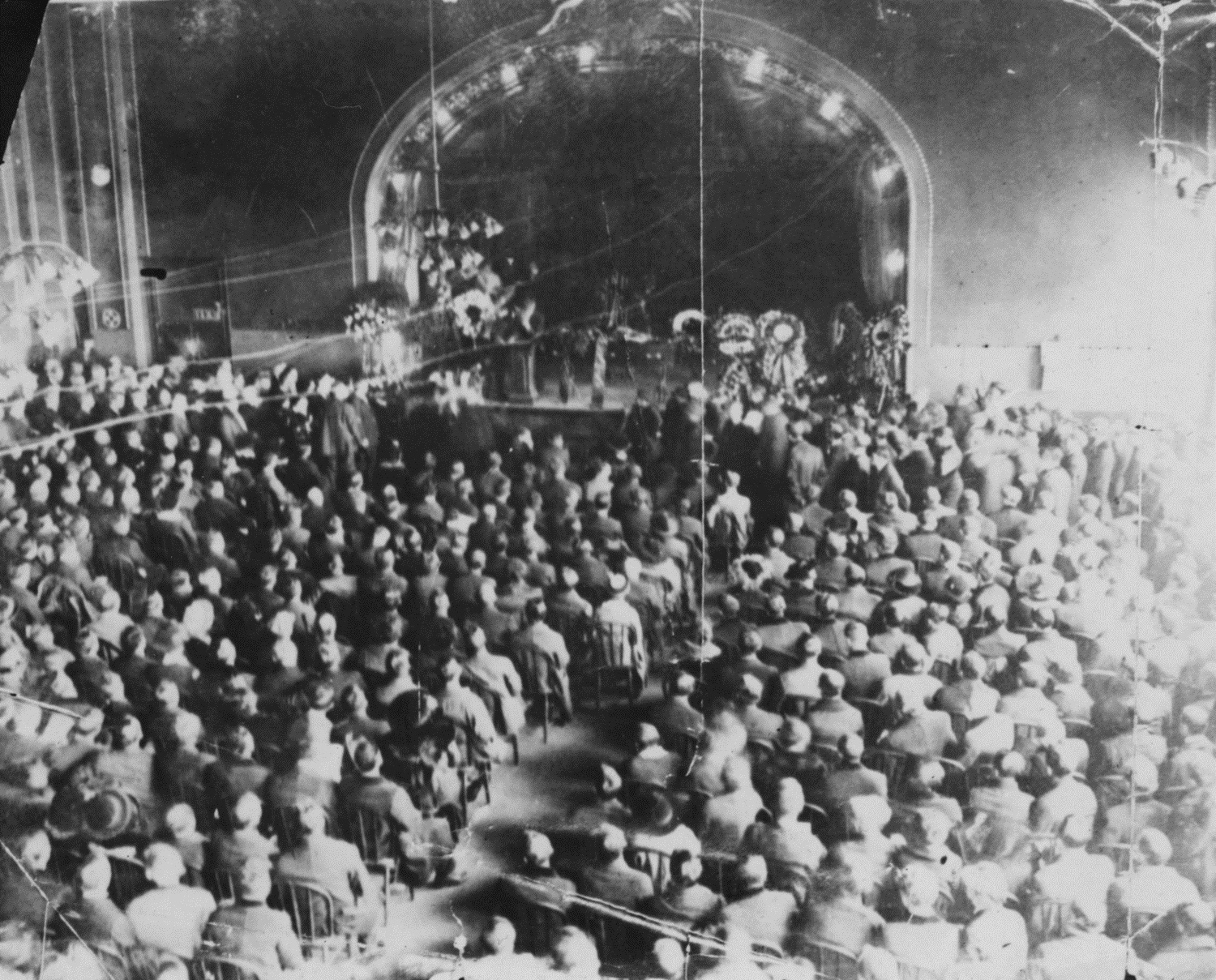

Approximately 30,000 mourners lined the streets for Hill’s funeral procession in Chicago, and at his request, his ashes were distributed to IWW locals in every state but Utah.

Hill Lives

Hill’s last words were, “Don’t mourn for me. Organize!”

A decade after his death, poet Albert Hayes wrote a poem that would become a union anthem:

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

Alive as you and me. Says I,

“But Joe, you’re10 years dead.”

“I never died,” said he.

“In Salt Lake, Joe, by God,” says I,

Him standing by my bed,

“They framed you on a murder charge,”

Says Joe, “But I ain’t dead.”

“The copper bosses killed you Joe,

They shot you Joe,” says I.

“Takes more than guns to kill a man,”

Says Joe, “I didn’t die.”

And standing there as big as life

And smiling with his eyes, says Joe,

“What they can never kill

Went on to organize.”

From San Diego up to Maine,

In every mine and mill,

Where working-men defend their rights,

It’s there you find Joe Hill.”

The poem was set to music in 1936, and was popularized in recordings by Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez, whose performance of “Joe Hill” at Woodstock in 1969 helped bring the legend to a new generation.

New Jersey rocker and union supporter Bruce Springsteen also brought the tune to life, performing it at a concert in Tampa, FL, on May Day, May 1, 2014.