April 30, 2012

Exploited Children Organize, Defeat Newspaper Titans

Just over a century ago, several thousand child laborers captured the nation’s attention when they took on two of the nation’s biggest newspaper publishers. Their struggle exposed the exploitation of children and inspired workers, both young and old, to fight for better pay and working conditions.

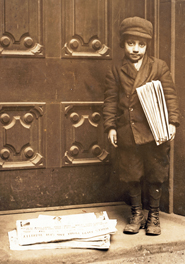

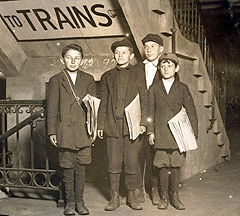

In the late 1890s, more than 100,000 homeless children roamed the rough-and-tumble streets of New York City. Many were orphans, runaways, or came from broken homes. Few social services were available; there were few restrictions on child labor, and there was no minimum wage. To get by, the kids performed odd jobs or found other work at low pay. About 10,000 young boys made a meager living selling newspapers on the streets.

In the late 1890s, more than 100,000 homeless children roamed the rough-and-tumble streets of New York City. Many were orphans, runaways, or came from broken homes. Few social services were available; there were few restrictions on child labor, and there was no minimum wage. To get by, the kids performed odd jobs or found other work at low pay. About 10,000 young boys made a meager living selling newspapers on the streets.

In the era before radio and television, the newspaper industry flourished, and many cities had multiple daily papers that published several editions a day. Most sold for just a penny and were distributed by “newsboys.”

Working directly for the publishers, children were the primary distributors for the papers. The newsboys usually paid about 50 cents for a bundle of 100 papers, which they resold.

The newsboys really had to hustle: The publishers refused to buy back unsold copies. The newsboys often hawked their wares from dawn to dusk — later if sales were slow. On average, they netted only about 30 cents a day — more if there was big news.

In New York City, the two biggest papers were the New York World, published by Joseph Pulitzer, and the New York Morning Journal, published by William Randolph Hearst. Both papers blamed Spain when the U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana harbor during a Cuban revolt against Spanish rule in February 1899. To capitalize on increased circulation during the Spanish-American War that followed, they raised their price to 60 cents per bundle.

In New York City, the two biggest papers were the New York World, published by Joseph Pulitzer, and the New York Morning Journal, published by William Randolph Hearst. Both papers blamed Spain when the U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana harbor during a Cuban revolt against Spanish rule in February 1899. To capitalize on increased circulation during the Spanish-American War that followed, they raised their price to 60 cents per bundle.

The newsboys offset the increased cost by selling more papers during the conflict, but after the war ended later that year, sales fell. Other papers reduced their price per bundle, but Hearst and Pulitzer continued to charge the newsboys 60 cents.

Infuriated, many newsboys refused to distribute theWorld and the Morning Journal.

On July 18, 1899, those who were still selling the paper found they had been shorted: After paying for full bundles, the newsboys received packages of less than 100. Calls for action against the two major publishers spread. Within days, the newsboys had formed a strike committee to determine strategy and had elected officers and appointed organizers.

The newsboys held parades to raise awareness of their plight, mobbed delivery wagons for Hearst and Pulitzer papers to prevent sales to strike-breakers, and demonstrated on the Brooklyn Bridge, bringing traffic to a standstill for several days.

Before the strike the public generally disdained the young vagabonds. “You see them everywhere,” one writer reported. They rend the air and deafen you with their shrill cries. They surround you on the sidewalk and almost force you to buy their papers. They are ragged and dirty. Some have no coats, no shoes, and no hat.”

Competing papers in New York and across the nation began lavishing coverage of the newsboys and their plight, creating more pressure on Hearst and Pulitzer.

The New York Tribune portrayed the strikers as colorful characters, quoting the likes of Race Track Higgens and Kid Blink in an oddly rendered dialect. The Tribune reported on a rally of several thousand newsboys and quoted Blink as saying, “Friens and feller workers, dis is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind.”

The New York Tribune portrayed the strikers as colorful characters, quoting the likes of Race Track Higgens and Kid Blink in an oddly rendered dialect. The Tribune reported on a rally of several thousand newsboys and quoted Blink as saying, “Friens and feller workers, dis is a time which tries de hearts of men. Dis is de time when we’se got to stick together like glue…. We know wot we wants and we’ll git it even if we is blind.”

Meanwhile, the newsboys’ strike spread across the New York metropolitan area, as well as to New Haven, CT, Fall River, MA, Providence, RI, and some other cities where Hearst and Pulitzer publications were sold.

The media titans fought back. Pulitzer tried to get the Yorkville police to arrest boys for “conspiracy” for distributing handbills that urged customers to boycott his New York World. To break the strike he and Hearst hired grown men to distribute their papers for a fl at rate of two dollars a day — more than the boys made in a week — and to beat up any newsboy who tried to stop them.

Their strike-breaking ploys didn’t work: Public sympathy had grown for the newsboys, and the publishers were losing big money as their circulation had fallen by two thirds. Hearst and Pulitzer quickly offered to drop their price to 55 cents per bundle, but the newsboys rejected their offer.

Just two weeks after the strike began, the publishers agreed to buy back unsold copies of their papers from the newsboys at full price. Though the price per bundle remained 60 cents, the boys had achieved their main bargaining goal, and the strike ended.

Legacy

Legacy

The newsboys strike caught the nation’s attention and raised public awareness about the exploitation of poor children. The work stoppage demonstrated that seemingly powerless people can gain respect and earn a better living. It also provided an example to the fledgling union movement during a time when organizing victories were difficult to achieve.

Though the newsboys strike happened more than a century ago, it was not forgotten: It inspired a popular comic book series in the 1940s, andNewsies, a 1992 Disney musical film about the boys’ struggles starring Robert Duvall and Ann Margret. A stage adaptation of the movie opened on Broadway in March 2012.