December 31, 2016

January-February Labor History Milestones

(This article first appeared in the January-February 2017 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Photo courtesy of the Lawrence History Center

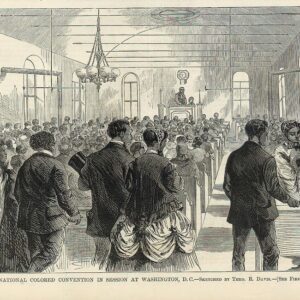

January 5, 1869 – The nation’s first labor convention of black workers was held in Washington, DC, with 214 delegates forming the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU). It was less than four years after the end of the Civil War and black workers were barred from being members of other unions. Nevertheless, they sought to improve their working conditions.

The union consisted of a variety of occupations, including mechanics, engineers, artisans, tradesmen and tradeswomen, all seeking equal representation in the workforce. Notable members included Frederick Douglass, who was elected union president in 1872. His newspaper, The New Era, was the official publication of the CNLU.

January 11, 1912 – The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organized the “Bread & Roses” textile strike of 23,000 workers, including immigrants from many different countries, in Lawrence, MA. A new state law changed the work week from 56 hours down to 54 hours per week. The mill owners docked the pay of the workers for the lost two hours, while at the same time speeding up the looms to make up for lost production. Textile workers walked off the job shouting “Short pay!” when they realized their weekly pay was cut.

Workers demanded a 15% wage increase, double pay for overtime work and a promise of no retaliation against the strikers.

The community rallied around the strikers. The story of the “walkout went viral in newspapers around the country, American laborers took up collections for the strikers and local farmers arrived with food donations,” wrote author Christopher Klein (The Strike that Shook America, History.com).

To help sustain the strike and its mass picket lines, families sent hundreds of their children out of Lawrence to New York and other states, where they stayed with family members or sympathetic working families.

Almost two months later, on March 2, a Congressional committee began hearing testimony about the strike after U.S. President Taft was compelled by the determination of the strikers to investigate. The testimony of the men, women and children about their brutal working conditions and small pay moved the legislators.

The mill owners settled shortly afterward, on March 14. Strikers received all they asked for, and with their victory raised the standard of living for workers across the country. By the end of the month, 275,000 textile workers in New England saw increases in their pay as other industries followed to avoid strikes from their own employees.

February 16, 1926 – Twelve thousand New York furriers belonging to the International Fur and Leather Workers Union began a 17-week strike. Strikers varied in background, including people of Italian, Jewish, Greek and African-American heritage, but they knew that by acting together they were in a better position to bargain and fought together for a 5-day work week with no reduction in pay.

Through the leadership of Ben Gold, strikers joined with members of various unions and allied organizations, including the New York State Federation of Labor, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union.

With the strikers’ unity and support from allies across the state, the employers saw they could not win and finally agreed to a new contract on June 11. The contract gave an unprecedented benefit package to the workers, including an end to overtime from December through August, time-and-a-half overtime pay for half-days from September to November, a 10% wage increase, 10 paid holidays and a ban on subcontracting.

It was also the first contract the union negotiated that included a 5-day, 40-hour work week, which in turn created more jobs and less unemployment. The strike strengthened the unity between the New York City and state-wide unions for decades to come. With that solidarity, they would all soon win the benefits the furriers had gained in their collective bargaining agreements. 4

Sources: Union Communications Services, ILR School, Cornell University, “Labor’s Untold Story” by Richard Boyer and Herbert Morais, History.com, and Peoplesworld.org.