April 30, 2015

May Day: Fighting for the Eight-Hour Day

workers filled Union Square in New York City on May 1 throughout

the 1930s. Shown here: 1933.

Chicago in the 1880s was a hotbed of labor organizing.

Fed up with the status quo, where industrial workers toiled long hours in squalid conditions, the International Working People’s Association formed in 1883 and dedicated its resources to establishing an eight-hour work day.

Led by Albert Parsons and August Spies, demands for an eight-hour day swept the nation. Workers from New York to San Francisco wore “Eight-Hour Shoes” and smoked “Eight-Hour Tobacco” – products made in factories that had already established an eight-hour workday.

A popular tune featured lyrics that summed up the cause: “We mean to take things over. We’re tired of toil for naught, but bare enough to live on; never an hour for thought. We want to feel the sunshine; we want to smell the flowers. We’re sure that God has willed it and we mean to have eight hours. We’re summoning our forces from shipyard, shop and mill. Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest and eight hours for what we will!”

At the American Federation of Labor’s 1884 convention, delegates adopted a resolution urging all workers to strike two years later, on May 1, 1886, to establish an eight-hour day.

Tension Mounts

Corporate-funded newspapers labeled the eight-hour movement communist, and Parsons and Spies quickly became targets.

“There are two dangerous ruffians at large in this city; two skulking cowards who are trying to make trouble. One of them is named Parsons; the other is named Spies,” a Chicago Mail editorial said. “Mark them for today. Keep them in view. Hold them personally responsible for any trouble that occurs. Make an example of them if trouble does occur.”

But no trouble occurred on May 1. Across the country, 340,000 workers took the day off, peacefully marching and singing through the streets. In Chicago, Parsons led 80,000 protesters up Michigan Ave.

Two days later, frustrated by the lack of discord, police beat the locked-out employees of nearby McCormick Reaper Works with billy clubs, as 300 replacement workers walked into the factory. At closing time, a crowd of locked-out workers were standing at the factory’s exit, when police ran at them, guns drawn.

Shots were fired into the retreating crowd. At least six were killed.

Spies later testified, “I was very indignant. I knew from experience of the past that this butchering of people was done for the express purpose of defeating the eight-hour movement.”

The Haymarket Affair

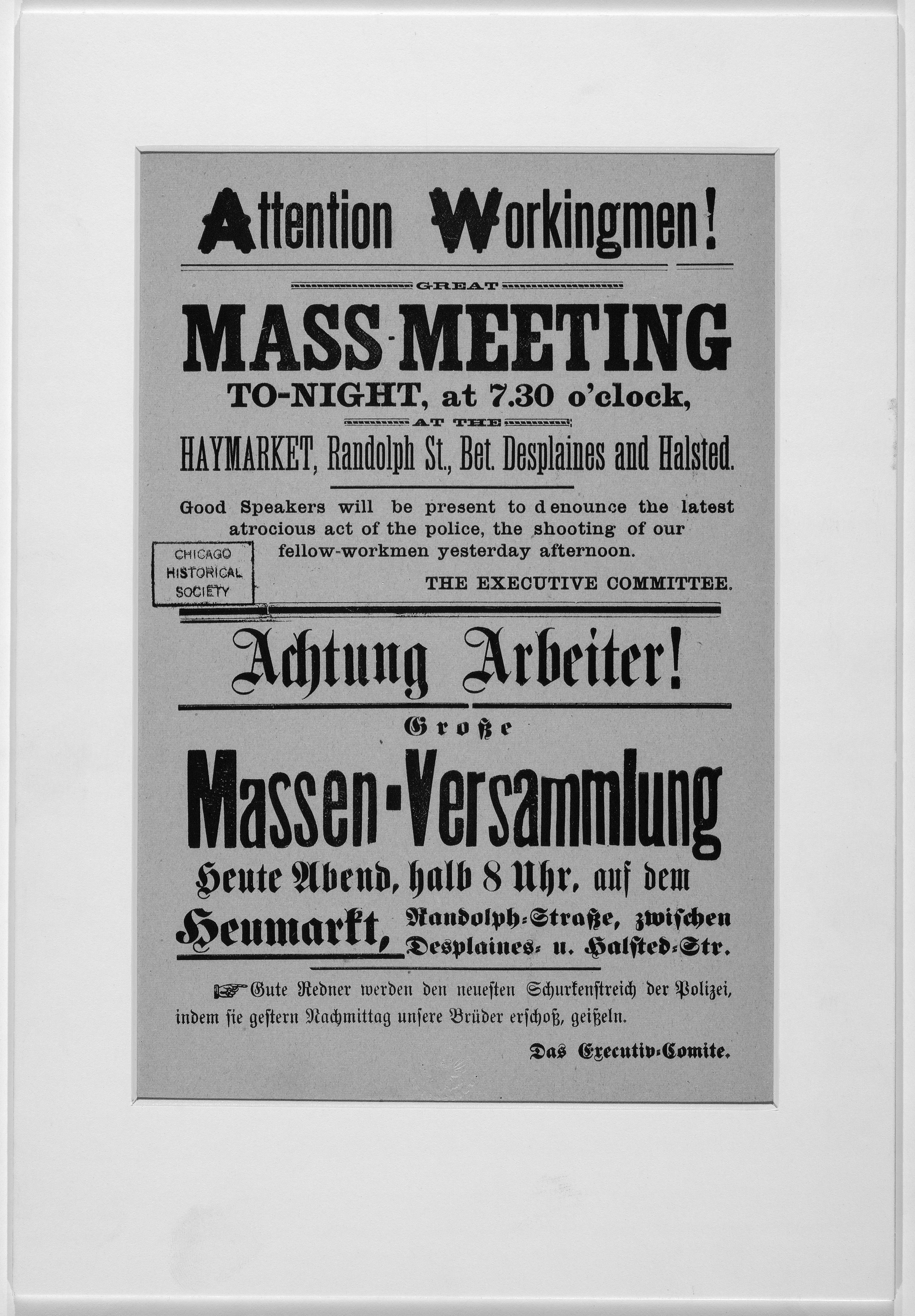

In the aftermath of the attack, outraged workers organized a rally in Haymarket Square to take place the evening of May 4. The event would later become known as “The Haymarket Affair.”

When Parsons arrived, a reporter told him, “We hear there’s going to be some trouble tonight.”

Unknown to Parsons and Spies, who were slated to speak, 180 police officers were mobilized at a nearby police station, under the command of Captain John “Clubber” Bonfield.

Parsons, Spies and British socialist Samuel Fielden addressed the crowd. The mayor, seeing that the rally was calm and beginning to disperse, told Bonfield and his men to stand down. They refused.

At about 10:30 p.m., as Fielden was speaking, police rushed to the speaker’s podium, smashing protestors with clubs, demanding they leave.

Fielden declared, “But we are peaceable!” when a bomb exploded. In the darkness and smoke, protestors scrambled to escape, only to be and clubbed by police and trampled by their horses.

When the smoke cleared, seven police officers and four workers lay dead. More than 100 were injured.

A ‘Frame Up’

The identity of the bomb-thrower is not known, but most believe the explosion was a set up, intended to silence the burgeoning labor movement.

Newspapers quickly reported that Parsons, Spies or Fielden threw the bomb and used the incident to incite anti-union and anti-immigrant fervor. They labeled the workers “anarchists” and “socialists” who sought to plunge the country into disarray. Labor leaders were arrested and union halls were raided.

Within days, Parsons, Spies and Fielden were indicted for murder of an officer killed during the chaos. Also indicted were labor leaders Michael Schwab, George Engel, Adolph Finscher, Louis Lingg and Oscar Neebe.

Of the group, only Parsons and Spies were at the scene when the explosion occurred.

Sham Trial

The trial began on June 21, with a jury of businessmen and their clerks – including a relative of a man killed at Haymarket. Some of the witnesses who testified were paid.

Testimonies were so full of contradictions that the state shifted its stance in mid-trial: The defendants did not throw the bomb, the state eventually conceded, but whoever did throw the bomb was inspired to do so by the defendants.

“If you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement… then hang us!” Spies told the judge. “Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you and in front of you and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.”

On Oct. 9, seven of the defendants were sentenced to death. Neebe was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Fielden and Schwab eventually received reduced sentences of life in prison. (Gov. John Peter Altgeld pardoned the three defendants in 1893, writing, “Much of the evidence given in the trial was pure fabrication.” Witnesses were “terrorized, ignorant men,” who police had threatened with “torture if they refused to swear to anything desired,” he said.)

Lingg committed suicide in his jail cell on the eve of his scheduled execution. Parsons, Spies, Engel and Finscher were publicly hanged on Nov. 11, 1887.

May Day Is Born

News of the tragedy sent shockwaves through the labor movement worldwide. In 1889, socialists declared May 1 International Workers Day – or May Day – to commemorate the Haymarket martyrs and build international workers’ solidarity. Today, May Day is celebrated in over 80 countries, with mass rallies and a day off from work.

But the holiday that was born in Chicago is not officially celebrated in the U.S. In 1894, Congress declared Labor Day a federal holiday, to be observed the first Monday in September. Although there was pressure to set the holiday on May 1, President Grover Cleveland – who wanted to distinguish Labor Day from Chicago’s workers’ uprising – refused.

In the 1930s, many U.S. unions organized May Day celebrations, with millions of workers marching in parades in New York and other cities. In 2006, hundreds of thousands immigrant workers marked the holiday with protests against an anti-immigration bill.

May Day, the international symbol of labor solidarity, lives!