December 31, 2014

A Look Back: The Charleston Five

Soon after dockworkers formed a picket line at the Port of Charleston, SC, in January 2000, five among them became the focus of worldwide protests and international solidarity – symbols of the fight for justice.

And after a 22-month battle, a groundbreaking victory over worker repression and racial discrimination was won in the anti-union South.

The five men, who were members of Local 1422 of the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), were among several hundred protesting because the Danish shipping company Nordana planned to unload cargo using non-union workers.

“Those jobs are something we cherish, and this operation was going to tear down our industry standards,” Local 1422 President Ken Riley told In These Times. “We’ve spent 40 years of hard work fighting for wages high enough that workers can send their kids to college and afford at least a middle-class standard of living. When we found out they were going non-union, we simply could not tolerate it.”

The events that followed the picketing would thrust five union members – four black and one white – into the forefront of a war waged by the state of South Carolina against unions in general and the black-led Local 1422 in particular.

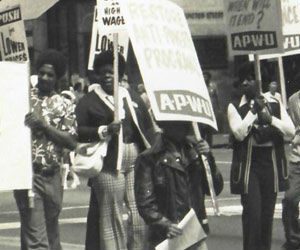

At protests demanding freedom for the Charleston Five, supporters stood behind empty chairs with enlarged photos of the men to highlight their absence. The Charleston Five spent nearly two years under house arrest.

Dispute on the Docks

Nordana had used union labor for 23 years when it announced in October 1999 that it would soon use non-union workers to handle its ships’ cargo. Although South Carolina has one of the lowest percentage of union members in the nation, all the dock workers at the Port of Charleston were members of Local 1422 – and almost all of them were black.

When Nordana’s ship docked on Jan. 20, 19 non-union workers were at the port ready to unload it. Picket lines were set up as the longshoremen mobilized to defend their union jobs. They were joined in an act of solidarity by the mostly white union for port clerks, ILA Local 1771, which swelled their ranks to nearly 300.

Police initially yielded to the workers as they headed for the picket lines, but South Carolina Attorney General Charles Condon organized a full-fledged assault. He called up 600 state troopers, highway patrolmen, and lawmen from across the state, flanked by police dogs and armored personnel vehicles. Helicopters circled overhead.

When Riley, president of Local 1422, appeared at the picket line, he was beaten by a state trooper and hospitalized. A melee followed.

Five dockworkers – Kenneth Jefferson, Elijah Ford Jr., Peter Washington Jr., Ricky Simmons and Jason Edgerton – were arrested and charged with conspiracy to incite a riot. A local judge dismissed the charges, but Condon denounced the decision and convened a grand jury to bring federal indictments against the workers.

Condon did not hide his disdain for the union members. Ignoring his own role in fomenting the fracas, he said his plan for “dealing with dockworker violence” was “jail, jail, and more jail.” He called for maximum bail, no plea-bargaining, and no leniency for union dockworkers. “South Carolina is a strong right-to-work state and a citizen’s right not to join a union is absolute and will be fully protected,” he said.

While awaiting trial the Charleston Five spent almost two years under house arrest, wearing electronic ankle bracelets and confined to their homes except to go to work.

It was no surprise that Condon took such a hard line. He harbored aspirations to run for governor and prosecuting members of the Local 1422 gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his anti-union, anti-black credentials.

Local 1422 had a reputation as an activist union, making it an ideal target for the ambitious state Attorney General. It had forged alliances with dozens of community organizations and was active in statewide progressive campaigns. Local 1422 played a central role in union organizing drives and in the campaign to remove the Confederate flag from atop the statehouse.

A police assault on a dockworkers’ picket line led to a melee.

Campaign to Defend the Charleston Five

But while Condon led the crusade against the Charleston Five, the labor movement rallied around the five men. The AFL-CIO launched a campaign to defend them, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars, forming alliances with Civil Rights organizations, and demanding justice. Speaking at a prayer vigil in 2001, Rev. James Lewis of the Covenant Missionary Baptist Church called the house arrest of the Charleston Five “brutal mistreatment” designed to “intimidate the right to organize.” Religious leaders vowed to “register voters and enlist the black community’s strong network of churches to support the longshoremen,” the Post and Courier reported.

Port workers on the West Coast represented by the International Longshore Workers Union pledged to shut down the docks when the case went to trial. Other unions organized defense committees and circulated petitions on behalf of the men.

The solidarity went global as Spanish dockworkers refused to unload Nordana cargo that had been loaded by non-union workers in Charleston. Other international unions joined the campaign, including the International Transport Workers Federation. Dockworkers in Denmark and Sweden pledged to take action the day the case went to trial.

On June 8, 2001, more than 5,000 union members descended on the South Carolina capital of Columbia, in the largest labor protest in South Carolina since the 1930s. Longshore workers were joined by supporters from the Communication Workers of America, Service Employees International Union, United Auto Workers, Teamsters, UNITE, and others.

A speaker from the Daewoo Auto Workers Union in South Korea addressed the throng of protesters, as did United Mine Workers President Cecil Roberts, who said he was willing to go to jail with the Charleston Five.

The Victory

After the rally in Columbia, supporters began organizing an International Day of Action for the opening day of the trial.

In October 2001, with headlines still dominated by the events of 9/11, Condon publicly compared the Charleston Five to the terrorists who demolished the twin towers. The backlash from that comment and other accusations of prosecutorial misconduct forced him to remove himself from the case a month before trial.

Protests for the Charleston Five continued to grow – until the state finally backed down. The prosecutor agreed in early November 2001 to drop felony charges after the five pled “no contest” to misdemeanor charges and paid a fine of $100 each.

“The campaign demonstrated that the union movement can win when we build broad alliances and use creative pressure tactics,” said Bill Fletcher Jr., national coordinator of the AFL-CIO’s Charleston Five Defense Committee. “We isolated the Attorney General and made him someone with whom no one wanted to be associated,” he said. “The union movement should have made much more of this victory than it did.”

Fortunately, the attack on dockworkers failed. The response – an unprecedented wave of solidarity that crossed color lines and national borders – continues to be an inspiration today.