June 30, 2002

A Look Back: Glen L. Howard

(This article was first published in the July/August 2002 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

The early days of the union movement were difficult times for workers who dared to fight for better wages and working conditions, and we should never forget the hardships that many early unionists suffered in order to win the right to collectively bargain that we enjoy today.

President Burrus recently received a letter from a gentleman in Georgia who recalls how in 1920, his father was fired by the Post Office Department for a letter he had written to Congress in support of higher wages and better working conditions for railway postal workers.

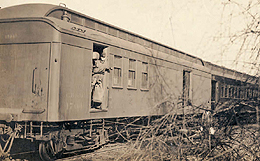

Lewis N. Howard told APWU that his father, Glenn L. Howard, worked as a railway postal worker based in Keokuk, IA. The senior Howard and a small group of men wrote a letter that was distributed to every member of Congress in support of higher wages and better working conditions for railway postal workers.

Their letter arrived at the height of the “Red Scare,” during the years following World War I when Americans feared the spread of the socialism that was taking hold in Russia and other European countries. Reactionaries accused immigrants and union organizers of spreading “radical socialism.”

An October 1919 editorial in The Railway Post Office, published monthly by the Railway Mail Association (an early postal union) lamented, “…there is certainly no question that labor, as a whole is being blamed for [the public hysteria about socialism and anarchism], and the blame is having its effect. There seems to be no distinction between organized labor men, radicals, ultra radicals, reds and unorganized labor men.” The Railway Mail Association was highly critical of the letter and its writers, but in contrast to other postal unions of its day, the organization was considered a company-dominated union that disassociated itself from labor activists.

Though what became known as “the Keokuk letter” is long lost, we do know it provoked a strong reaction in Washington, DC. “The [stuff] hit the fan,” recalls Lewis Howard, who also reports that one influential congressman was reported to say, “we will show these people who is boss,” presumably by ordering the letter signers’ firing.

The letter was even denounced by some unionists who feared actions that “rocked the boat” during a time when people felt they had to be careful about voicing their opinions lest they be called “reds.”

The same editorial cites an unnamed Republican senator who denounced the labor movement by saying, “America is not Austria or Russia, and it’s time that every man, woman and child living under our flag should realize that. There is no room here for [unionism], there is no reason for the ultra-socialist thought, and God knows this is the one spot on the universe” that should repudiate such ideas.

No one knows exactly what Howard and his colleagues wrote in the letter to earn the condemnation they received, but is unlikely that they were radical socialists.“My father and his father before him were lifelong Republicans,” reports Lewis Howard.

Red or Republican, the elder Howard lost his job and his pension after 17 years of service to the Post Office.He was forced to take on odd jobs for the next few years, and he, his wife, and their five children suffered economic hardship because he dared to speak up for workers during a repressive and fearful time.

Howard had no recourse, no way to fight back, no way to appeal his firing, which was the case for many workers who struggled for their rights in the early days of the labor movement.

A review of the Postmaster’s Annual report for 1920 makes only a brief mention of a strike by railroad worker during the previous spring. The report does mention that management suppressed the strike, which is referred to in the report as “interference with the transmission of the mails,” by gathering the names of the people responsible and bringing “such cases to the attention of local United States district attorneys with request that offenders be prosecuted for obstruction of the mail if the facts warranted.”

In the early 1930’s Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed into law the National Labor Relations Act, which since its passage has offered workers certain protections against employer retaliation for participating in union activity.

After continued hard times during the Depression, Glenn Howard died in 1943 while Lewis Howard was away serving in the Navy in the South Pacific. Lewis Howard lives on, along with his bride of 62 years, in Loganville, GA, and at the age of 87 is writing his autobiography. He reports that his story will be full of his personal recollections, which, like his father, include being fired for union activity.

The APWU salutes you, Mr. Howard, for the sacrifices you and your family made for the union cause and for your family’s patriotic service to our nation during difficult times.