December 31, 2015

Paul Robeson: Internationally Acclaimed Performer, Champion of the People

(This article first appeared in the January-February issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

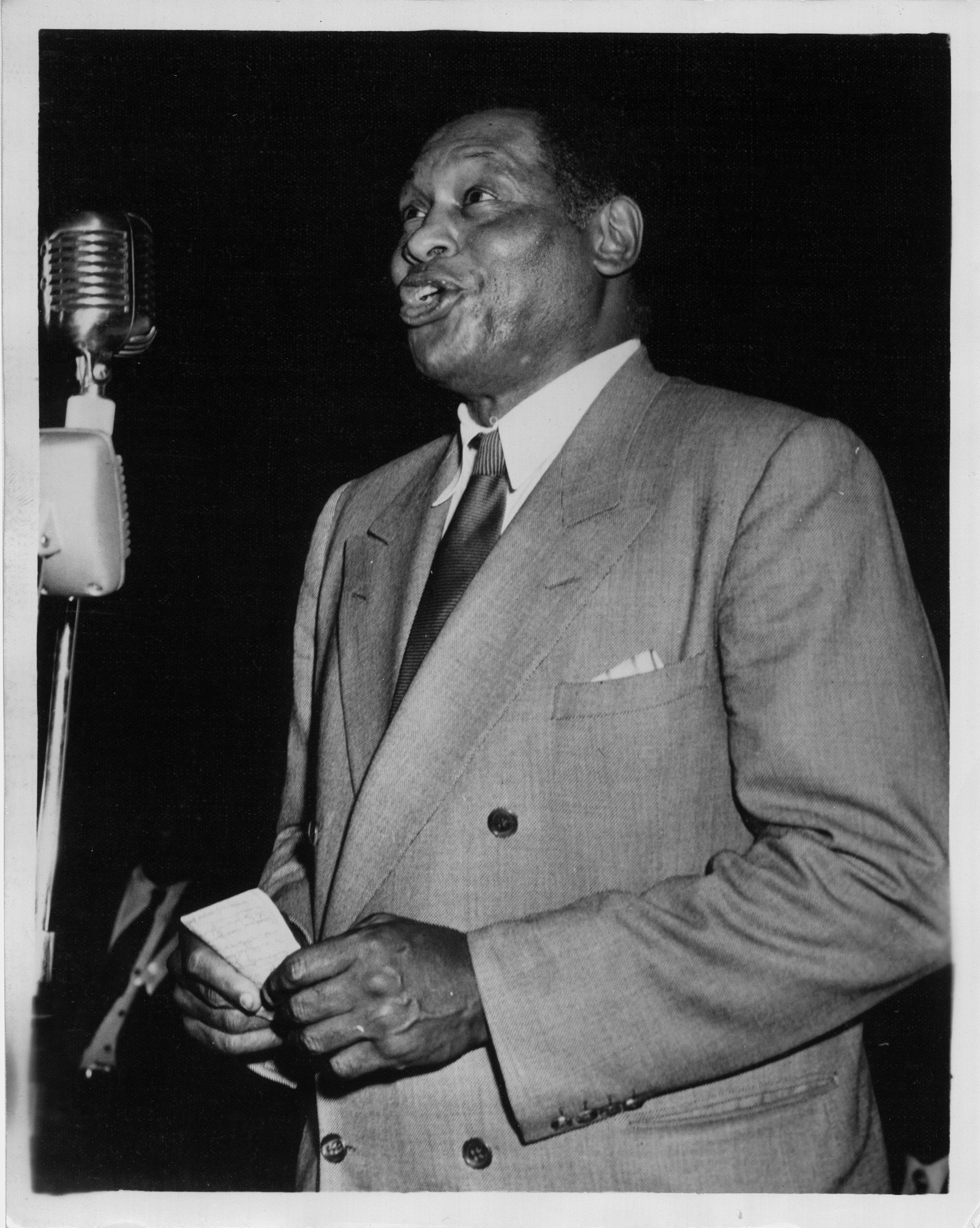

Photo courtesy of Robeson Family Trust and Marilyn Robeson

Paul Robeson was an internationally acclaimed singer and actor, an outstanding athlete and intellectual, an outspoken advocate of racial justice and workers’ rights, and a fierce opponent of colonialism and fascism.

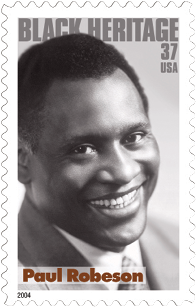

He was a beloved figure to millions of fans worldwide – both for his enormous talent and for his support of righteous causes. In 2004, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp in his honor as part of the Black Heritage series.

But at the height of his career, as McCarthyism took hold, Robeson’s inspirational message would not be tolerated. He was blacklisted and persecuted during one of the darkest periods in our nation’s modern history.

Son of a Runaway Slave

The son of a runaway slave, Robeson was born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, NJ.

At 17, he received a scholarship to Rutgers University, becoming the third African-American to attend the school. He earned top honors for his debate and oratory skills and soon became a star athlete, winning 15 varsity letters in four sports – football, baseball, basketball and track.

Robeson graduated valedictorian and had a short professional football career, but decided to attend Columbia University Law School, where he earned a degree in 1923 and met his wife, Eslanda Cardozo Goode. Robeson worked briefly at the Stotesbury and Miner Law Office but, offended by the discrimination he encountered, he soon quit.

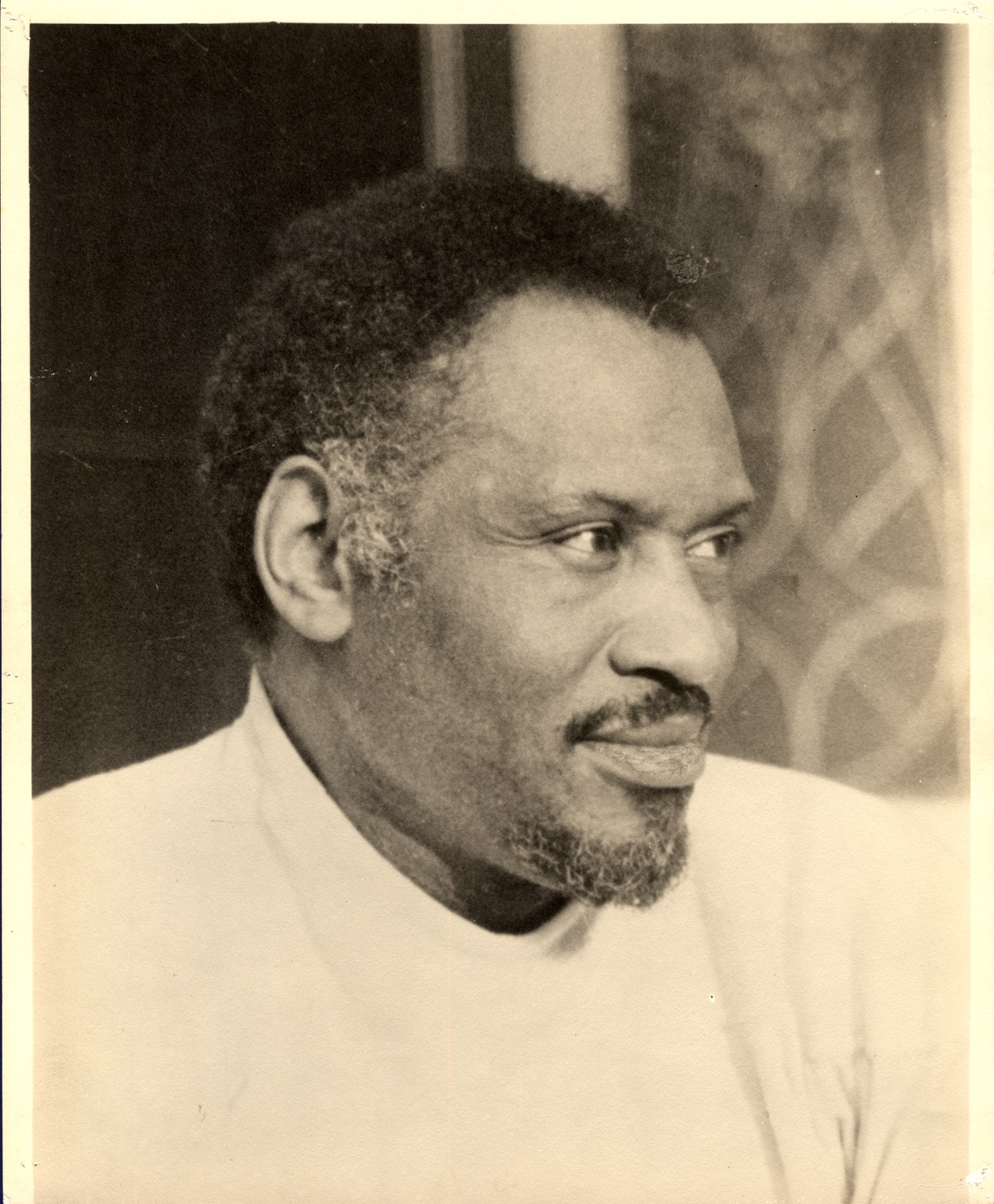

Photo courtesy of Robeson Family Trust and Marilyn Robeson

Encouraged by his wife, Robeson pursued his other passions: acting and music. Over the next 20 years, he enjoyed an illustrious career in theater and film, captivating audiences around the world with his unmistakable bass voice.

Robeson and his family lived in Europe and New York City, mingling in glamorous social circles, as he starred in productions of Shakespeare’s Othello, the musical Show Boat, and films such as Proud Valley. He is probably best known for his stirring rendition of “Ol’ Man River,” which became the standard for future performers.

Robeson on a stamp in 2004. ©USPS

Singing in Solidarity

Robeson used his talents to champion the causes he believed in. He was an ardent opponent of racial discrimination and a leader of the American Crusade to End Lynching. He was the first major concert artist to refuse to perform before segregated audiences, foregoing many lucrative offers to tour in the South as a result.

He also immersed himself in the fight for workers’ rights.

“At the heart of his labor activism was a burning desire to see black and white workers unified, without which, Paul felt, union movements could easily be destroyed,” his granddaughter, Susan Robeson, wrote in The Whole World in His Hands: A Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson.

He walked hundreds of picket lines and, in honor of his displays of solidarity, was designated an honorary member of many unions, including the Fur and Leather Workers Union, National Maritime Union, Food and Tobacco Workers Union, International Longshoreman and Warehouse Union, International Union of Mine Mill and Smelter Workers, and United Public Workers.

When members of the United Auto Workers launched a wildcat strike at a Detroit Ford plant during a contract dispute in 1941, company bosses lured black workers from the South to act as strikebreakers, promising them high wages.

Photo courtesy of Robeson Family Trust and Marilyn Robeson

As tensions escalated, Robeson stepped in. Calling for unity, he sang, spoke to thousands of workers gathered downtown, and shook hands at the plant’s picket line. “The best way my race can win justice, is by sticking together in progressive labor unions,” Robeson said.

The UAW signed a contract with Ford Motor Company soon after Robeson intervened.

In a speech at the International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union Caucus in August 1948, he said: “In traveling around the country, it is quite clear that the struggle for economic rights, the struggle for higher wages, the struggle for bread, the struggle for housing, has become part of the wider political struggle… There has to be basic change.”

He capped off his speech with a rousing rendition of the labor ballad “Joe Hill.”

‘The Soil from Which I Spring’

Due to his views on racial and social justice, which were considered radical at the time, Robeson was barred from many conventional venues. Undeterred, he found creative ways to reach audiences.

Photo courtesy of Robeson Family Trust and Marilyn Robeson

Between 1939 and 1956 he sang to African-American tobacco workers in the Carolinas and in schoolyards and Baptist churches; he performed around campfires in Hawaii for Filipino and Japanese immigrant pineapple workers; before Jewish garment workers in Catskill bungalows and Bronx social halls; for black and white stevedores and factory workers in union halls in Memphis; to Finnish-American miners in social clubs in Minnesota; for Mexican-American miners in Colorado and Arizona; to thousands of auto workers outside factories in California and Michigan; before black Panamanian government workers in a Panama City stadium, and for Canadian miners and metal workers on the border between Washington state and Vancouver.

“It seemed strange to some that having entertained some status and acclaim as an artist, I should devote so much time and energy to the problems and struggles of working men and women,” Robeson said. “To me, of course, it is not strange at all. I have simply tried to never forget the soil from which I spring.”

“The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice,” he said.

Photo courtesy of Robeson Family Trust and Marilyn Robeson

At Home and Abroad

Robeson spent much of the 1940s advocating for civil rights and economic justice – both in the U.S. and abroad.

He traveled to Spain during the Spanish Civil War and was a leader in the global fight against fascism. He fought for independence for India, promoted African self-rule, and spoke out for peace in Paris. He was a voice for peace and freedom that was heard in every corner of the world.

Despite his worldwide popularity, as McCarthyism flourished, he was labeled a traitor by the American press.

“From 1949 the FBI put pressure on concert halls not to allow him to sing,” his granddaughter told BBC News in 2014. “No recording company would issue a contract and he disappeared from the radio.” His name was stricken from the college All-American football teams and news footage of him was destroyed.

In August 1949, an outdoor Robeson concert in Peekskill, NY, was disrupted by a racist, pro-fascist bat-wielding mob. Hundreds were injured, 13 of them seriously.

And in 1950, although he hadn’t been charged with a crime, the State Department revoked his passport and President Truman signed an executive order forbidding him to travel outside the country. “Committees to Restore Paul Robeson’s Passport” were quickly organized. His right to travel was restored 8 years later when the Supreme Court ruled in an unrelated case that denial of a passport on the basis of political beliefs is unconstitutional.

Following that victory, Robeson performed a “comeback” concert at New York’s prestigious Carnegie Hall and returned to Europe for a triumphant five-year tour.

Plagued by poor health in his later years, he died in 1976 at the age of 77.

Robeson lived his life in a way that can be summed up in a quote from his book Here I Stand:

“I learned that the essential character of a nation is determined not by the upper classes, but by the common people, and that the common people of all nations are truly brothers in the great family of mankind… I learned that there truly is a kinship among us all, a basis for mutual respect and brotherly love.”