February 28, 2015

Rose Schneiderman Organizes Garment Workers in New York

Rose Schneiderman was a trailblazer for workers’ rights in the Lower East Side of New York City at the turn of the 20th Century. She organized and co-founded several unions, was a friend and advisor to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and was a champion for rights still being fought for today.

Twenty-year-old Rose Schneiderman had been working at the Hein & Fox cap factory on West Third Street for just two months when a fire broke out on Dec. 2, 1898, 13 years before the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

The blaze destroyed Schneiderman’s workplace and two adjacent buildings. It also destroyed many of the sewing machines, which workers were forced to purchase via an installment plan that automatically deducted fees from their paychecks.

Management reportedly received thousands of dollars in insurance, but workers never saw a cent.

The working environment was poor before the fire and wages and conditions deteriorated even further after the factory was relocated. Hours were long – 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. – and the tasks were tedious. Schneiderman and dozens of other young Jewish immigrant women stitched linings into golf and yachting caps, earning three to 10 cents per dozen. If they worked hard, they made about $5 a week.

Rather than simply commiserate with her co-workers, Schneiderman decided to take action. She and a few other women attended a meeting of the all-male National Board of United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers Union, where they requested help organizing their workplace. The union told them to gain commitments from 25 women, which they did within a matter of days. Meeting the proper requirements, the women were officially initiated as a new local.

Progressive Roots

Born Rachel Schneiderman in Savin, Poland on April 6, 1882, she was the first of four children in a religious family. Her parents both worked in the sewing trades.

Schneiderman’s parents defied norms by sending her to Hebrew school – which at the time was attended almost entirely by boys. In 1890, they immigrated to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Just two years later, Schneiderman’s father passed, plunging the family into poverty. Though her mother was a seamstress, she did not earn enough to keep the family under one roof. Rose and her siblings had to live in an orphanage for several years until she got on her feet.

Schneiderman reluctantly left school after sixth grade in 1895 to help provide for her family. She worked as a cashier in a department store before starting her life-changing work at the Hein & Fox cap factory.

A Born Leader

By 1907, Schneiderman – 4’9” with flaming red hair – was heavily involved in the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). After just one year, she was elected vice-president of the New York chapter, where she worked full-time organizing for the union.

In 1909, Schneiderman was active in the “Uprising of the 20,000,” one of the first massive strikes organized by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) to protest poor working conditions.

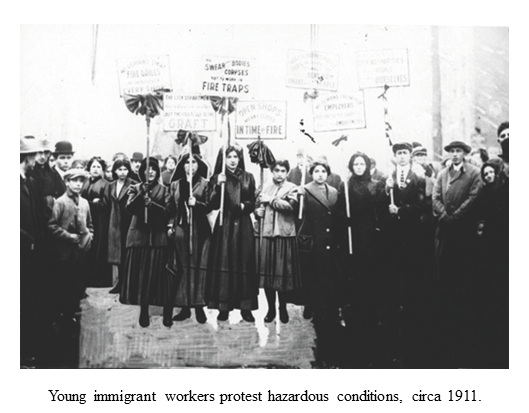

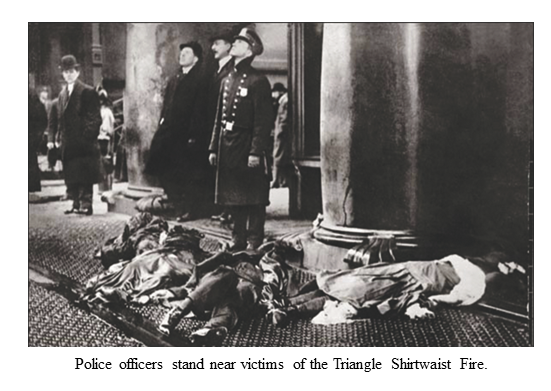

In 1911, as a result of those poor conditions, 146 garment workers were killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the deadliest industrial disaster in New York City history. All of the victims were young, female immigrants, who perished from the flames or jumped to their death because stairwells were locked. In its aftermath, Schneiderman spent a year on the ILGWU’s staff.

“I would be a traitor to those burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship,” she said to a crowd of New Yorkers shortly after the fire. “Every year, thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred.”

By the late 1910s, as president of the New York chapter and the national WTUL, Schneiderman lobbied for minimum-wage and eight-hour-day legislation. In 1921, she helped organize for the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry, where students were introduced to ideas that were considered radical, such as feminism and social justice.

A powerful friendship began when future First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt joined forces with the WTUL in 1922. Schneiderman kept Roosevelt abreast of the issues facing women workers, the challenges the trade union movement faced, and problems related to labor-management relations. In return, Roosevelt chaired the WTUL finance committee, donating the proceeds from her 1932-1933 radio broadcast to the union and promoting it in her columns and speeches.

In 1933, Schneiderman became the only woman appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt to the labor advisory board of the National Recovery Administration (NRA), where she made sure workers received fair treatment in codes written to standardize industry practices. She called the work “exhilarating and inspiring,” though she was unsuccessful in eliminating provisions that allowed lower wages for women doing the same work as men.

Schneiderman was appointed secretary of the New York State Department of Labor in 1935, after portions of the New Deal were declared unconstitutional. After eight years and lacking stimulation, she retired from the post. But Schneiderman remained president of the WTUL until it disbanded in 1950, and continued to be active in the New York League. She finally retired in 1955 at the age of 73.

During her retirement, Schneiderman wrote her autobiography and made occasional appearances on radio shows and at union events. She never married, but treated her nieces and nephews as if they were her own children. Schneiderman died on Aug. 11, 1972, at the Jewish Home and Hospital for the Aged in New York City. She was 90.

A Cultural Legacy

Amidst the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire’s tragic aftermath, Schneiderman said, “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist – the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with.”

The phrase, “Bread and Roses,” was turned into a poem decades later and was set to music and sung by various artists, including Judy Collins and John Denver.

Always ahead of her time, Schneiderman was an early feminist, speaking out against sexual segregation in the workplace; trying to unionize not only industrial women but white-collar and domestic workers; and regularly calling for state regulation of factory, office, and home working conditions. She also argued for issues that are still being debated today: equal pay for equal work legislation, government-funded childcare and maternity leave.