June 30, 2013

To Stand Up, Auto Workers Sat Down

On Dec. 30, 1936, workers in Flint MI began a historic “sit down” strike that helped win union representation for auto assembly employees across the nation.

Showing remarkable pluck, savvy, and solidarity, Flint’s auto workers occupied a key General Motors facility for 44 days and forced one of the nation’s largest and most obstinate employers to bargain with the newly-formed United Auto Workers union.

The Flint auto workers helped bring to fruition the promise of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which — following generations of labor strife — established workers’ rights to organize unions and bargain collectively for better wages and working conditions.

The strike that began in Flint marked a major turning point in labor history and helped lift millions of exploited workers out of poverty.

Hard Times

The Great Depression made earning a living tough in the 1930s, especially for auto workers, who faced declining pay, layoffs, arbitrary firings, and daily pressure to speed-up production.

In 1935, most auto workers earned only half of what it took to support a family of four. To make ends meet during the 3- to 5-month layoff between model production years, they often depended on loans from their employer — for which they were charged interest.

Working conditions were deplorable. “There were no safety requirements, no medical help on-site. Lots of workers lost fingers and hands and some were killed,” UAW retiree Ed Henry told the Gaylord Herald Times in 2012. “There was no compensation for the injuries or for the family if they got killed.” In July 1936, temperatures on the work floor topped 100 degrees for a week, but the bosses at several plants refused to slow production. Hundreds of auto workers across the state died in four days.

Pay was based on productivity, and bosses frequently reduced the pay per piece.

“We would start out with a new rate, arbitrarily set by the company time-study man and work like hell for a couple of weeks, boosting our pay a little each day,” Clayton W. Fountain wrote in Union Guy. “Then the timekeeper would come along one morning and tell us that we had another new rate, a penny or two less than it had been the day before.”

With growing unrest on the work floor, GM was determined to prevent its workers from organizing. Only about 100 among the tens of thousands of workers in Flint had joined the UAW, but management employed a legion of spies and thugs to discourage workers from signing up.

A New Strategy

Union leaders knew their ranks included spies and that GM controlled the city’s politicians and police force. So instead of distributing leaflets and holding meetings in public places, they signed up workers at their homes and sent membership information directly to UAW national headquarters to keep information from management.

By late 1936, the union was gaining strength, and GM knew it.

After workers halted production several times at Flint’s Fisher Body Plant Number One in November to protest speed-ups and wage cuts, the company planned to move key operations to a less unionized area.

But by then the workers were prepared to take the company on — and had a plan to bring the company to its knees. Union members knew that GM had just two factories that produced the dies used to fabricate car bodies: one in Flint that produced the parts for Buick, Pontiac and Oldsmobile, and one in Cleveland that produced parts for Chevrolet. The union planned to stop production at both plants in early 1937, to force the company to switch from piece work to hourly pay, and to recognize the union.

But when the night shift arrived for work at Fisher Body Plant Number One in the early hours of Dec. 30, the workers discovered that the plant’s body-stamping dies were being moved onto railroad cars. At an emergency meeting the workers decided that if the equipment left, their jobs did, too, and they decided to act right away.

Rather than picketing outside the plant, the workers decided to seize the factory — to prevent equipment from being moved and to keep management from sending in strikebreakers.

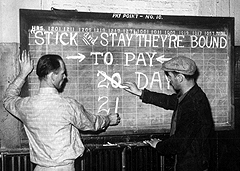

At 8 p.m. on Dec. 30, the workers stormed the building, halted the trains, barricaded themselves inside the plant, and prepared for a long siege. They erected defenses and elected committees to handle defense, health and sanitation, education, recreation and other matters.

Outside the plant, the union prepared food, which was brought into the factory by city bus drivers, who were grateful for UAW support during a recent strike of their own. Union members and supporters also conducted around-the-clock pickets; provided child care; handled media relations; coordinated hundreds of volunteers, and collected donations.

When police attempted to storm the plant on Jan. 11, the workers greeted them with fire hoses. And when police fired tear gas into the plant, members of the women’s auxiliary broke windows to give strikers relief from the noxious gas.

After several failed attempts to get into the plant, the police hastily withdrew rather than battle 400 women from the union’s Emergency Women’s Brigade, who marched through the police lines singing, “Hold the Fort.”

The following day, newly-elected Gov. Frank Murphy deployed Michigan’s National Guard – not to evict the strikers, but to protect them from the police and company thugs.

By then, strikes had also broken out at Fisher Body Plant Number Two in Cleveland and at other key GM factories in Michigan, St. Louis, Buffalo, Oakland CA, and elsewhere.

Although the strikers were gaining power, some GM plants were still operating, most notably Flint’s Chevy Plant Number Four, the company’s largest engine production facility. On Feb. 1, 1937, strikers easily took over that plant after a ruse convinced the company that a different facility had been targeted. By then more than 125,000 strikers had closed 50 GM plants.

Victory

Victory

GM knew it was beat, but still refused to talk directly with the UAW. United Mine Workers President John L. Lewis stepped in to represent the UAW in negotiations, and Gov. Murphy acted as an intermediary.

On Feb. 11, GM finally agreed to recognize the UAW as the exclusive bargaining representative for union members nationwide. Leaving the plant after 44 days, the victorious sit-down strikers were greeted by thousands of cheering supporters.

Following similar struggles, Chrysler workers won a similar agreement in March 1937, as did Ford workers in June 1941. In the next year, UAW membership grew from 30,000 to 500,000, and wages increased by as much as 300 percent.