October 31, 2002

(This article was first published in the November/December 2002 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

In the 90 years since it departed England on its only journey, the R.M.S. Titanic has remained of unwavering great interest, with the focus tending towards its design or the actions of its many famous passengers.

But the greatest ship of its day was also a floating mini-economy. On the maiden voyage alone, it was supposed to provide two weeks of comparatively well-paid work for nearly 900 “crew,” including a few postal clerks: R.M.S. stands for “Royal Mail Steamer,” which indicates that the luxury liner was legally commissioned to carry mail.

When Titanic collided with an iceberg, the postal workers rushed to their posts to try to save the shipment they had been entrusted with — and it probably cost them their lives. And since the ship’s owner was an American, J.P. Morgan, a U.S. government inquiry into the disaster was launched.

Congress later immortalized the heroic efforts of the three U.S. Post Office employees.

The postal workers who sorted and cancelled mail aboard ships were the cream of the work force. American sea post clerks in the early 20th Century earned about $1,000 a year, an excellent wage at a time when “another day, another dollar” was still a meaningful expression.

While the postal workers’ 14-hour days may seem excessive today, most of the crew worked most of their waking hours. It wasn’t until after the passage of the Seaman’s Act of 1915 – enacted in part because of publicity over working conditions on Titanic — that a “two-watch” system was instituted.

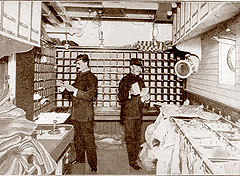

The postal clerks were unique among the crew members in that their work had nothing to do with operating the ship or serving passengers. There also were two British postal workers on the voyage, and the sea post clerks’ working conditions were not grand. The sorting rooms were deep in the ship and even more cramped than those in railway mail cars.

Work in Progress

One of the clerks’ first tasks was to store the bags that would not require their attention at sea.When Titanic began its voyage, the five postal workers set to distributing letters and packages from Great Britain and the European mainland.

The clerks no doubt had most of the pre-sorted mail stored before they left Ireland (Titanic’s last stop before heading for New York), so their routine during the four days the ship was on the open sea was concerned largely with sorting mail to be ready for immediate dispatch upon arrival at New York Bay’s Quarantine Station, where all incoming ships were detained for a health inspection.

Mail offloaded from a luxury liner typically was well on its way long before all passengers had disembarked.

Clerks John Starr March and Oscar Scott Woody had 15 years of experience with the U.S. Railway Mail Service, and may have been members of the Railway Mail Association, which was organized as a mutual insurance concern in 1897. (In 1917 it would declare itself a labor union by affiliating with the American Federation of Labor, the AFL.)

Before he took to the sea, the third American, William Logan Gwinn, had spent six years in the Foreign Mail Section. Gwinn was in England, assigned to the ship Philadelphia, when he learned that his wife Florence was deathly ill. He was granted a transfer to Titanic to get home more quickly. (As it turned out, Florence Gwinn recovered.)

At 48, John March was the oldest of the American sea post clerks and was, in effect, Titanic’s postmaster. This was his eighth year at sea; while on assignment the previous year, his wife had died, prompting his two adult daughters to renew their pleas for him to seek work elsewhere in the postal system.

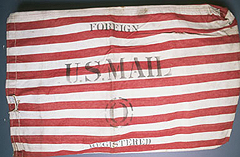

The postal clerks were celebrating Oscar Woody’s 44th birthday in their private dining room several decks above their work area when Titanic collided with the iceberg. They rushed to the mail room and began trying to move the registered mail — 200 bags’ worth — to a higher deck.

Near the bottom of the 10-tiered ship, the sorting room started taking in water immediately after the accident. Within 15 minutes of the collision, the sea post office’s lower room was nearly filled with water. According to a ship’s steward, Albert Theissinger, all five postal clerks worked feverishly in the sorting room just above, closing registered mail sacks and carrying them to higher decks.

Theissinger, among those who answered the call to help move the mail to higher ground, gave up when it became apparent the water was rising too swiftly. “I urged them to leave their work,” the steward recalled. “They shook their heads and continued at their work. It might have been an inrush of water later that cut off their escape, or it may have been the explosion. I saw them no more.”

Traditions of the Service

Among the five clerks, only Woody’s and March’s bodies were recovered. March’s pocket watch was found to have stopped ticking at 1:27, suggesting that it wasn’t immersed until about two hours after the clash with the iceberg.

Since evidence suggested that the doomed sea post clerks worked beyond the call of duty, Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock included them in his Annual Report for 1912:

“The bravery exhibited by these men in their efforts to safeguard under such trying conditions the valuable mail entrusted to them should be a source of pride to the entire postal service … The loss of the men is deplored, but their example is a fine one for the traditions of the service and consistent with their previous records.”

Hitchcock called on the government to do something for the workers’ families and Congress responded by appropriating a total of $6,000, or about two years’ salary to each of the families of the American clerks.

These families fared far better than most affected directly by the Titanic tragedy. Surviving crew, for example, not only were deprived of wages for the second-half of their round-trip job, they were paid only for five days of the original voyage: Under a common policy of steamers of the era, they had “finished” their assignments at the moment the great ship went down.