February 29, 2016

Women Workers Defy Their Boss and Win a Union

(This article first appeared in the March-April 2016 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Factory boss Willie Farah said he’d rather be dead than see his company go union.

But the women workers in his clothing factory had something up their sleeves.

Between 1972 and 1974, thousands of Farah Manufacturing Company workers walked off the job, organized a nationwide boycott, and won a union. Eighty-five percent of the strikers were women, and almost all were Chicano, or Mexican-American.

Their fight for a union also changed the way the women saw their role in society: They became leaders – at work, at home, and in their communities.

Recollections of their battle were recorded in the 1977 book, Women at Farah: An Unfinished Story, by Laurie Coyle, Gail Hershatter and Emily Honig. (When the book was written, many of the strikers still feared retaliation, so their names were not published.)

Working Conditions Worsen

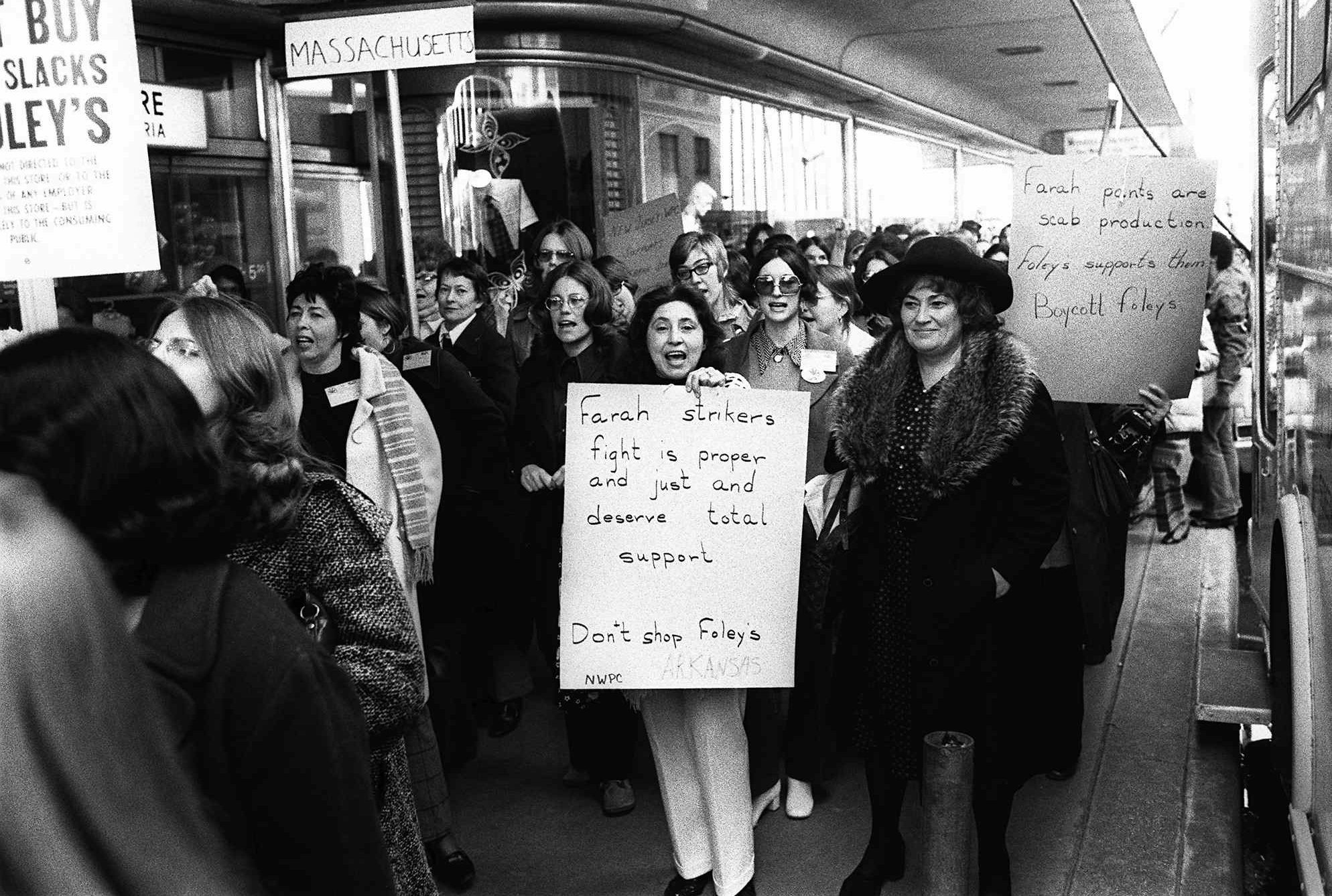

line supporting striking Farah workers in Houston on Feb. 10, 1973.

Farah had factories across Texas and New Mexico, and was El Paso’s second largest employer. The Texas city, located near the border of New Mexico and Mexico, has – and had – a mostly Chicano population.

After Willie Farah took over the company from his brother in 1964, he opened seven more plants and imposed unattainable production quotas. Working conditions quickly worsened.

“They would go to a worker and say, ‘This girl is making very high quotas… And if you can’t do it, we’ll have to fire you,’” recalled one worker. Bosses did this throughout the shop, trying to turn employees against each other.

Farah often rode a bicycle through the plants urging employees to work faster.

Undercover Organizing

Farah workers first attempted to organize in 1968, with the help of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). Bosses responded by showing videos on company time of alleged union corruption. Nevertheless, garment cutters voted to unionize in October 1970.

An organizing drive among seamstresses and other workers soon began. To avoid retaliation, the campaign was conducted undercover. With their jobs constantly threatened, women hid union cards in their purses, met secretly in bathrooms, and whispered plans in the halls.

Organizing efforts reached a fevered pitch in 1972.

In March, 26 workers at one of the El Paso plants walked out and Farah fired them on the spot. Weeks later, workers in San Antonio were fired for participating in a union rally in El Paso. Afterwards, more than 500 San Antonio workers walked out in protest.

On May 9, thousands of machinists, shippers, cutters and seamstresses – who used to tremble when their supervisors yelled – marched out of the El Paso factories with their heads held high.

“When I started walking outside, all the strikers were out there, yelling, they saw me, and golly, I felt so proud, ’cause they all went and hugged me. And they said, ‘We never thought you were one of us.’ And I said, ‘What do you think? Just because I’m a quiet person,’” said a worker named Alma. “But it was beautiful! I really knew we were going to do something. That we were really going to fight for our rights.” Workers at other plants soon followed.

The strike was on!

Boycott

In June the strikers launched a boycott of Farah clothing, forming picket lines at El Paso plants and stores that carried Farah merchandise.

Support for the workers was initially weak: Passersby accused picketers of wanting a government handout. Farah called the police on the strikers, who harassed them with dogs, and the company tried to block press coverage of the strike.

But the workers could not be stopped.

ACWA sent organizers to El Paso and sponsored classes on labor history and union procedures. The union also started a Farah Relief Fund, and allotted workers $30 in weekly strike benefits.

Churches, Students, Chicanos…and APWU

The strikers reached out to their community for support. They contacted local churches, which responded enthusiastically. Father Jesse Muñoz allowed the workers to hold union meetings in church facilities and participated in a national speaking tour to promote the boycott. Bishop Sidney Metzger relayed the strikers’ struggles to other bishops across the country, winning wider support.

Dozens of Chicano organizations, student groups, and progressive organizations across the country also embraced the boycott. One of those was the newly formed APWU.

During the union’s 1972 National Convention in New Orleans, 2,000 APWU members picketed outside two department stores that carried Farah products. The action was led by Moe Biller, who was then president of the Manhattan-Bronx Postal Union

A great tradition was born: The APWU has held a major solidarity action at conventions ever since.

More to Life Than Cooking and Cleaning

The Farah strikers who traveled across the country on speaking tours were encouraged by the support they received and began to see themselves in a new light. The women, many of whom had never before left Texas, realized there was more to life than cooking, cleaning, and working in the factory.

“If I had not walked out, I would not have been able to realize all those things about myself,” said one woman.

Strikers in the tight-knit community developed a strong sense of solidarity. “Here the whole neighborhood, you know, the majority of us were on strike!” recalled one striker.

The overwhelming support frustrated Farah. He lashed out, publicly blaming the Catholic Church for his trouble with the union.

Victory

By 1974, the boycott was taking a financial toll on the company. Sales dropped from $156 million in 1972 to $126 million.

In January 1974, the National Labor Relations Board charged Farah with “trampling on the rights of his employees,” and ordered the company to reinstate workers who had been fired for union activity – with back pay.

Finally, on Feb. 23, Farah recognized ACWA as the bargaining agent for the workers and the boycott ended. After negotiations, a contract was ratified on March 7.

Empowered

The fight for a union transformed the women who took part, empowering them to take on new responsibilities in the workplace and at home.

They embraced their newfound independence. “As you grow up, you’re used to always being told what to do. For years I wouldn’t do anything without asking my husband’s permission,” one woman said. “I was able to begin to feel that I should be accepted for the person that I am.”

The struggle also impacted strikers’ children. “You know, I think the strike has made my kids more outspoken. Maybe some would call it disrespect. I don’t,” said one worker. “Like my son – if somebody…gives him a hard time, I expect him to stand up and speak for his rights.”

One striker connected the workers’ struggle to the growing women’s movement, “I believe in fighting for our rights, for women’s rights! Why did I put up with it all these years? Why didn’t I try for something else?”

The Farah strikers reached for the heavens and in the process won a union and so much more.