August 31, 2008

Andrew Furuseth: ‘The Abe Lincoln of the Sea’

(This article was first published in the September/October 2008 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

The struggles of workers aboard commercial ships have seldom received much public attention, but some of history’s worst employment practices occurred at sea, where sailors were often subject to forced labor, brutal discipline, deplorable working conditions, and little certainty about being paid.

When American sailors began to unionize in the 1800s, they found a champion in Andrew Furuseth, a humble Norwegian immigrant who led their struggle for 50 years, helping to overturn centuries of maritime law against the determined opposition of powerful ship owners and their allies in Congress.

Grateful sailors of his day called him “the Abe Lincoln of the Sea.”

Leaving Home

Born to a large family in Anders, Norway, in 1854, at age 8 Furuseth was sent to work on a farm to help his struggling family make ends meet. The farm owner liked him enough to pay for an education at a Lutheran school. In 1870, the teenager left the farm to work as a grocery-store clerk and to study for admission to a military academy. His application ultimately was rejected, but he had gained a useful skill: the ability to speak several languages.

In 1873, with few other opportunities, Furuseth, like many other young men in coastal towns around the world, went to sea. For six years he worked and lived on Norwegian, German, French, and American ships, where he saw men beaten, put in chains, and denied basic necessities, often merely for getting on the wrong side of a ship’s mate. In 1880, Furuseth walked away from a British ship docked in San Francisco, eventually taking a job with a fishing boat plying the Oregon Coast.

Five years later, on a port call in San Francisco, he learned that fellow sailors had formed the Coast Seamen’s Union (CSU) in response to a deep wage cut by ship owners. The strong-willed Furuseth had had enough of the deplorable way sailors were being treated, and he joined the union as a way to fight back.

‘Crimps and Buckoes’

Ship-owners’ associations controlled hiring for all vessels with a “grade book” system through which they blackballed union sympathizers as well as any able seamen who refused to kowtow to officers, complained about beatings by “buckoes” (ships’ disciplinary staff), or refused to put up with the food, quarters, long hours, or safety conditions, or had previously quit a ship for any of these reasons.

Ship-owners’ associations controlled hiring for all vessels with a “grade book” system through which they blackballed union sympathizers as well as any able seamen who refused to kowtow to officers, complained about beatings by “buckoes” (ships’ disciplinary staff), or refused to put up with the food, quarters, long hours, or safety conditions, or had previously quit a ship for any of these reasons.

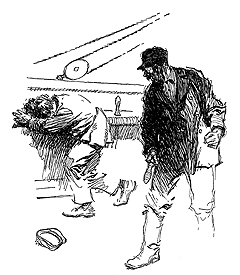

And when sailors were not willing to sign on for a particular voyage or ship, it was a common practice for “crimps” (company hiring agents) to kidnap, or coerce men to come on board through trickery, intimidation, or violence.

Crimps would “recruit” in the city’s saloons and boarding houses. Paid “by the body” when labor was short, particularly during the California and Alaska gold rushes, crimps were known to recruit sailors by rendering them unconscious, delivering them to a ship, and forging their signatures on a work contract. The practice became so well known that a common destination of ships with large numbers of abducted crew members, Shanghai, became the term to describe it.

Regardless of how he got there, a member of a crew often found that he could collect only a small portion of his wages, at the captain’s whim; that he owed money to the crimp who “recruited” him; and that if he tried to quit during a voyage he could be arrested — under U.S. and international maritime laws this could happen anywhere in the world.

In countless cases, seamen who expressed a desire to quit were beaten and shackled until they returned to port, or hunted down and tried for desertion if they tried to escape service mid-voyage.

Fighting for Sailors’ Rights

Furuseth took the helm of the CSU in January 1887, just two years after joining, when he was elected its secretary-treasurer.

The union had successes in organizing West Coast seamen, but gains against recalcitrant ship owners were temporary, due to the volatility of the market. Based on the results of early job actions, Furuseth determined that the only way for sailors to prevail against the ship owners, grade books, and crimps was to change the laws that gave them the upper hand.

Furuseth first merged the CSU with the Steamships Sailors Union to create what is known today as the Sailor’s Union of the Pacific (SUP).He also sought to unite with other fledgling maritime unions under the National Union of Seamen of America (an AFL craft union) and the International Seamen’s Union.

In 1898, he led the union fight for passage of the White Act, which officially abolished corporal punishment and imprisonment for ship desertion while in U.S. ports. But ship owners always managed to circumvent the White Act and a series of other laws, and continued to exploit sailor labor.

In 1908, Furuseth was elected as president of the International Seamen’s Union of America. The ISUA was a federation that included the SUP and unions representing Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, and Great Lakes sailors. He held the organization’s top post for 30 years, and led efforts to build public and congressional support for a comprehensive bill to guarantee sailors’ rights.

It was invariably tough going, especially in the face of steadfast opposition from wealthy shipping interests. Marine disasters such as the 1912 sinking of the Titanic, however, raised awareness about the importance of a qualified crew, and Furuseth is given the bulk of the credit for the passage of the Seamen’s Act of 1915, which has been known to successive generations of sailors as the “Magna Carta of the Sea.”

A Sea Change for Workers

The Seamen’s Act abolished once and for all imprisonment for desertion on American ships anywhere at sea, and required the U.S. to abrogate treaties that allowed the practice. The act helped drive up wages around the globe: Foreign ship owners were forced to pay American pay scales to replace crews that quit in U.S. ports.

Among other provisions, the law also limited sailors’ work days to nine hours while in port; set minimum standards for food and living space; required sufficient lifeboats on all vessels; required that most crew speak the same language as their officers; and required a minimum percentage of the crew to be qualified Able Seamen.

Among other provisions, the law also limited sailors’ work days to nine hours while in port; set minimum standards for food and living space; required sufficient lifeboats on all vessels; required that most crew speak the same language as their officers; and required a minimum percentage of the crew to be qualified Able Seamen.

Another important provision of the law decreed that sailors no longer could allot part of their wages to creditors before joining a vessel. “This sounded the death knell to crimps, shanghaiers and shady boarding housekeepers who had preyed on the sailor, taking a ‘mortgage’ on his wages in exchange for food, lodging, drinks and clothes,” said a recent retrospective by the Seafarers International Union.

The union made significant wage and membership gains during a World War I shipping boom, and a Furuseth-led strike in 1919 resulted in even higher wages for deep-sea sailors.

Furuseth remained the ISUA’s president until he died in 1938, at 83. He was the first union leader to have been laid in state at the U.S. Department of Labor. A World War II merchant-marine ship and a seamen’s training academy have been named for him.

The SUP today is an affiliate of the Seafarers International Union, AFL-CIO, which represents merchant mariners working on deck, in engine rooms, and as stewards on commercial containerships, tankers, military-support ships, tugboats and barges, and passenger and other U.S. vessels on the oceans, Great Lakes, and inland waterways. The International Longshoremen’s union, AFL-CIO, represents dock workers and others who help move ships’ cargo.