June 30, 2016

With Help from Women’s Movement, Canadian Postal Workers Score Big Win for Families

A little solidarity can go a long way. Thirty-five years ago, Canadian postal workers launched a 42-day strike for paid maternity leave – and won. The Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) was the first federal union in Canada to win 17 weeks of paid maternity leave – and they did it by building an alliance with the women’s movement.

As strike preparations began, CUPW President Jean-Claude Parrot reached out to hundreds of women’s organizations. Initially the groups were slow to respond, but as the strike progressed they responded by joining a media campaign that dominated the headlines.

The unity of the workers and women’s organizations resulted in one of the most important benefits Canadian citizens enjoy today. It’s a benefit Americans are still fighting for: In 2015, just 21 percent of U.S. companies offered paid maternity leave.

Not Falling for It

To prepare for negotiations, the union produced seven background papers, outlining the significance of each contract demand, including the demand for paid maternity leave. The papers were distributed to shop stewards and other union activists so they could build support among union members.

In those days, the CUPW negotiated contracts with the Treasury Board, whose president, Don Johnston, believed a previous settlement was too costly. Johnston seemed to want “to give the Postmaster General a lesson in how to bargain with postal workers,” Parrot wrote in his memoir, My Union, My Life.

When the CUPW demanded 20 weeks of paid maternity leave, the board refused and launched a campaign of disinformation, attacking union leaders in the media and accusing them of being inflexible.

The board’s refusal was perplexing: CUPW’s demand wouldn’t have been costly. In fact, 20 weeks of paid maternity leave would only have cost the equivalent of about a 2-cent- per-hour wage hike, and the employer had already offered a 50-cent raise at the bargaining table. (Unlike their American counterparts, the Canadian unemployment insurance system included a provision for maternity leave.) Pregnant women were already eligible for 15 weeks of unemployment insurance at 60 percent of their salary. The union demanded that the Treasury Board agree to “top-up” unemployment coverage to the new mothers’ full salary and pay their full salary for an additional five weeks.

The Treasury Board tried to placate the CUPW by promising that maternity leave was on the government’s legislative agenda.

But the workers didn’t fall for that line. “We felt all women had an interest in this, and we were determined to win this right for our members at the bargaining table,” Parrot explained. “We have no intention of waiting for the government to decide on this issue,” he said at the time. “We have the right to negotiate paid maternity leave and we will not wait to be told later on that such leave will be unpaid.”

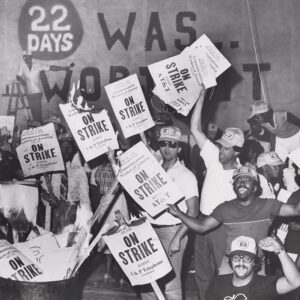

With the Treasury Board refusing to bend, CUPW called for a strike vote, and 84 percent of members voted in favor. (Canadian postal workers have a legal right to strike.)

Workers walked off the job June 29, 1981.

Help from Friends

The postal workers’ demand for paid maternity leave became a battle for the hearts and minds of the Canadian people.

Newspapers across the country ran editorials about paid maternity leave, supporters and opponents debated the issue in letters to the editor, and proponents phoned in to radio shows.

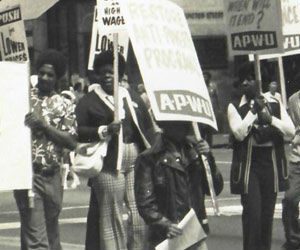

Postal workers and the women’s movement were an integral part of the battle. The National Action Committee on the Status of Women (NAC) distributed an educational flyer supporting the demand and urging others to join the cause. The group also demonstrated in front of the South Central postal plant in Toronto and held press conferences about the strike all around Toronto and Halifax. The Vancouver-based feminist group Bread and Roses held a solidarity march to the picket line.

“Women deserve full economic protection for the short time they leave the work force to recuperate from childbearing and to establish a relationship with the newborn child,” wrote Dr. Gail Hutchinson, president of the London (Ontario) NAC in a letter to the editor of The London Free Press. She championed “the fundamental right to be financially secure for the birth of a child.”

Jeanie Campbell was a member of the London Local for 27 years. Now retired, she had four children before she began working at the post office – and lost three jobs because of her pregnancies. “That was not right and I knew it was not right,” she said. Campbell walked picket lines that summer and called radio talk shows, explaining the union’s position. “Every local across Canada worked together to get the job done,” she said.

“It was really an exciting time. Women were beginning to get voices in unions,” recalled retired CUPW member and activist Marion Pollack in a documentary, A Struggle to Remember, Fighting for Our Families, made by the Worker’s History Museum.

Throughout the strike, the government’s lack of concern about keeping the mail moving disturbed Parrot. After a few weeks went by, the Treasury Board offered a wage hike of 70 cents per hour, but wouldn’t budge on 2-cent paid maternity leave.

“It showed that it was still out to get postal workers and it showed how out-of-touch the government was with the needs of workers, especially women,” he said.

Sweet Victory

Eventually, the Treasury Board conceded and agreed to include 17 weeks of paid maternity leave in the collective bargaining agreement. During the first two weeks, workers were paid 93 percent of their weekly wage, with up to 15 additional weeks of unemployment benefits, also topped up.

The victory is particularly sweet for Campbell because her granddaughter is a postal worker currently on paid maternity leave. “She doesn’t have to worry if she has to make ends meet or fight for her job. It makes me feel good,” Campbell said, choking up.

Why did the board finally yield? Parrot said the board had lost the public debate on the issue and “were seen as fighting against women on an issue that was costing them very little.” Before the strike began, the board erroneously concluded that postal workers wouldn’t be willing to engage in a work stoppage. Eventually they realized the union leadership had “no intention to compromise”

“They really chose the wrong issue to take us on,” Parrot said.

When the postal workers returned to work on Aug. 12, they were the first national union in Canada to win paid maternity leave.

In 1985, the Canadian Labour Code extended the benefits to include 24 weeks of parental leave, beginning at birth, plus eight weeks of “compassionate care leave.” In 1990, modifications to the Unemployment Insurance Act allowed new parents an increase of 10 weeks on top of the initial 15 weeks. In 2001, the combined maternity-parental benefit period was doubled to 50 weeks.

Now 83, Campbell said, “It will always make me proud that we did this – even the men, too. Solidarity!”