December 31, 2008

Isaac Myers: Pioneer of the African-American Trade Union Movement

Editor’s Note: The African-American trade-union movement goes back further than most people realize, with its roots planted before the Civil War. Among the Civil War pioneers was Isaac Myers.

It’s not unusual for a labor leader to have humble beginnings. Isaac Myers started out literally at the bottom, applying sticky sealant to the hulls of oceangoing ships. But he had a natural leadership style, and while his determination to prosper ultimately resulted in contributions to the labor movement, it also found him success as a supervisory clerk in a wholesale operation, as an entrepreneur, and in civic arenas: He would become president of a chamber-of-commerce-style men’s association and of a building-and-loan cooperative.

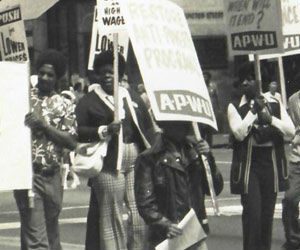

Throughout his life, he took part in progressive efforts that showed he was an advocate of equality in the workplace. While the organizations he was affiliated with would rise and fall in the decades to come, the dreams of Myers and millions of other minority workers never died, and their cause would be advanced by succeeding generations of labor and civil rights activists.

On the Waterfront

Not much is known about Isaac Myers’ early life, except that he was born to free parents, in Baltimore in 1835. He came of age at a time when the city’s schools denied entry to all African-American children, slave or free, but Myers learned to read and write under the tutelage of John Fortie, a Methodist minister.

When he was 16, Myers’ parents arranged for him to become an apprentice to Thomas Jackson, an African-American ship caulker who was quite well-known. Work was plentiful on the Baltimore waterfront, and many freemen worked as caulkers, applying pitch and gum to seal the seams between planks and beams on wooden-hull vessels. Myers learned his craft quickly, and by age 20 had been placed in charge of a crew that caulked large clipper ships.

Myers stayed in the trade for about a decade. He then opened a grocery business in the early 1860s, but he kept close ties with his colleagues in construction and maintenance at the port.

Baltimore shipyards employed many free blacks. They also employed slaves leased to shipyard owners. One was Frederick Douglass, who worked as a caulker in 1836 and 1837, just before he escaped to freedom. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, there was plenty of work, and white dockworkers had opportunities beyond caulking. Most freemen worked as caulkers or as skilled or semi-skilled carpenters and longshoremen.

Baltimore shipyards employed many free blacks. They also employed slaves leased to shipyard owners. One was Frederick Douglass, who worked as a caulker in 1836 and 1837, just before he escaped to freedom. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, there was plenty of work, and white dockworkers had opportunities beyond caulking. Most freemen worked as caulkers or as skilled or semi-skilled carpenters and longshoremen.

In 1838, African-American workers formed the Caulkers Association, one of the first black trade unions in the U.S. This was a true union: Bargaining collectively with Baltimore’s shipyard owners, it made significant gains.“Caulkers were paid very well and were seldom refused wage increases since the Association monopolized the market,” wrote Bettye C. Thomas in the Journal of Negro History (1974). “They were also able to dictate the conditions under which they would work.”

In the late 1850s, the caulkers were being paid $1.75 per day — which was more than many white workers earned in similar trades. The high pay did not go unnoticed by shipyard owners and the influx of immigrant workers seeking jobs on the waterfront. In 1858, the historian Thomas wrote, “riots were instigated against black workers.”

In response, some shipyard owners refused to hire black caulkers, and the situation was tense for several years. At the end of the Civil War, in 1865, white workers staged a successful strike that forced shipyards to dismiss African-Americans. Approximately 1,000 dock workers lost their jobs.

Community Business

By then, Myers was married, with three children, and was a high-ranking clerk at a wholesale-grocery business. In response to the white workers’ successful strike, he organized a group of black and white businessmen to create a new shipyard, the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company, a cooperative that employed 300 black workers, and some white tradesmen, at $3 a day.

The company ceased operations in 1884. “The venture was successful, ”W.E.B. Du Bois observed in 1902, “until it was found that, instead of having purchased outright, the yard had only been leased for 20 years.”

Myers had served as a board member and the company’s unofficial spokesperson, but he dedicated most of his efforts to the nascent black trade union movement. In 1868, as president of the Colored Caulker’s Trades Union Society of Baltimore, he began reaching out to black unionists in other trades and other cities to press for inclusion in the National Labor Union, which had been formed two years earlier as the first major national federation of local trade unions.

National Labor Organization

Advocating an eight-hour day and the creation of a labor-focused national political party, the NLU recruited both skilled and unskilled workers, as well as farmers, but it was not committed to bringing women and African- American and Chinese workers into the fold.

Advocating an eight-hour day and the creation of a labor-focused national political party, the NLU recruited both skilled and unskilled workers, as well as farmers, but it was not committed to bringing women and African- American and Chinese workers into the fold.

Though an NLU committee had recognized that “the interests of labor were one, any discrimination on either racial or religious grounds was harmful to all working men,” many of its constituent unions objected to allowing membership to blacks, and the issue remained unresolved.

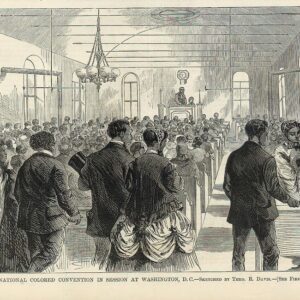

At its national convention in Philadelphia in 1869, the NLU invited Myers and a delegation of other black union leaders from around the country to make their case for inclusion. Myers addressed the gathering, making an impassioned plea for equal treatment and the acceptance of black workers by organized white labor:

“I speak today for the colored men of the whole country … when I tell you that all they ask for themselves is a fair chance; that you shall be no worse off by giving them that chance…The white men of the country have nothing to fear…We desire to have the highest rate of wages that our labor is worth.”

The NLU convention mulled Myers plea for two days, then rejected it, but offered affiliation to black unionists in a separate organization. Losing the round but hoping to win the fight eventually, Myers and others formed the Colored National Labor Union. “The watchword of the colored man must be, ‘organize,’ ”Myers would say.

Legacy

Both the NLU and the CNLU disintegrated during the Depression of 1873. By then, Myers had ceded leadership of the organization to Frederick Douglass. In the final days of the CNLU, however, Myers had been on an organizing tour in the southern U.S. Soon, he had launched the Colored Men’s Progressive and Cooperative Union, which despite its name admitted women, and advanced membership to workers without regard to race. It was a true industrial union, and welcomed members of all occupational backgrounds.

Both the NLU and the CNLU disintegrated during the Depression of 1873. By then, Myers had ceded leadership of the organization to Frederick Douglass. In the final days of the CNLU, however, Myers had been on an organizing tour in the southern U.S. Soon, he had launched the Colored Men’s Progressive and Cooperative Union, which despite its name admitted women, and advanced membership to workers without regard to race. It was a true industrial union, and welcomed members of all occupational backgrounds.

In the 1870s, Myers stepped up his involvement in the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, and worked as a Customs Service agent and as a postal inspector. After a few years in the south, he returned to Baltimore in 1880 to operate a coal yard. He served as a leader of several African-American community organizations, and was editor of the Colored Citizen, a weekly newspaper. He died in 1891, at the age of 56.

In June 2006, Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park opened in Baltimore’s Fells Point, with “living classroom” exhibits on shipbuilding traditions of the Chesapeake Bay and the local African-American community during the 1800s.