August 31, 2006

Postal Workers ‘In the Line of Duty’

(This article was first published in the September/October2006 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

Postal workers are sworn to uphold the Constitution and protect the mail.

Since 1775, we have honored our pledge to defend the security of the mail, on which much of our nation’s commerce and communication system has always depended. From the dangers of transporting mail on horseback across the wild frontier to sorting it in the current era of chemical and biological terrorism, we have always faced the risks and fulfilled our mission with pride.

The 230 years of commitment is honored by an exhibit at the National Postal Museum, a part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. “For more than two centuries, America’s postal workers have maintained a constant and vigilant watch over every home and business,” states the introduction to “In the Line of Duty: Dangers, Disasters and Good Deeds.”

“In times of need, they have responded with selfless deeds and willingly risked their lives for the safety of others.”

At Ground Zero

When terrorists struck on Sept. 11, 2001, postal workers close to Ground Zero in New York City were among those able to help survivors amid the chaos, confusion and continuing dangers of fire and falling rubble.

When terrorists struck on Sept. 11, 2001, postal workers close to Ground Zero in New York City were among those able to help survivors amid the chaos, confusion and continuing dangers of fire and falling rubble.

Remarkably, no one at the adjacent post office was injured, even though part of the jet that hit the World Trade Center’s north tower landed on the roof of the building that housed the Church Street Station, and many of its windows were blown out. Many of the city’s postal workers dropped what they were doing and offered water to stunned survivors or transported them to shelters and train stops in USPS trucks. Mail service throughout the city was restored within days, and became symbolic of New York’s comeback.

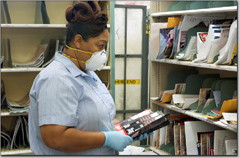

In the wake of 9/11, letters containing anthrax bacteria were mailed to several news-media outlets and the offices of two U.S. senators. These terrorist attacks, too, exacted a toll, with five people killed, including postal clerks Joseph Curseen Jr. and Thomas Morris Jr., both infected while processing mail in Washington. There were 18 known anthrax cases, with one deadly envelope carrying a Sept. 18 postmark. (APWU members Morris and Curseen died Oct. 21 and 22, 2001, respectively.) The crime remains unsolved.

Sortation Uncertainties

The mail was long suspected of carrying diseases — a fear that yellow fever, smallpox, influenza, etc., could be transmitted through letters and packages led to practices such as quarantine and crude sanitation efforts that often proved destructive to the contents of letters and packages.

The mail was long suspected of carrying diseases — a fear that yellow fever, smallpox, influenza, etc., could be transmitted through letters and packages led to practices such as quarantine and crude sanitation efforts that often proved destructive to the contents of letters and packages.

Today we know that many of the maladies are spread by mosquitoes or viruses passed through direct human contact. For many years, however, public health officials and the nation’s postmasters ordered that mail leaving places with known outbreaks of disease be “fumigated with formalin gas or sulphur fumes, treated with carbonic acid, sterilized and baked in assorted attempts to thwart epidemics.” To help contain a yellow fever outbreak in 1888, postal workers were ordered to perforate all mail leaving Florida with spiked paddles, scatter it across wire shelves in a railway mail car, and finally bathe it in a sulphurous gas before distribution.

Decades before the notorious “Unabomber” captured the nation’s attention, an alert New York City mail clerk,Charles Caplan, became a national hero after reading a newspaper during a train-ride home following his shift. On May 5, 1919, Caplan read an article about a package containing a bomb that had injured a maid in the home of Thomas W. Hardwick, who had just finished a term in the U.S. Senate. The newspaper article described a package similar to some that the mail clerk had seen that day at his duty station.

“Caplan rushed back to his station and commenced a frantic search for parcels resembling the Hardwick bomb,” the Smithsonian exhibit notes. “When the dangerous mission was finished, thirty-six mail bombs had been recovered and thirty-six tragedies averted.”

Hazards From Here to There

From the earliest days of the U.S. Post Office, workers performed the duties of today’s APWU members, sorting and distributing the mail, and getting it from station to station. The frequent attacks on couriers (including the riders of the short-lived Pony Express), stagecoaches, and railway cars that moved the mail across the expanding nation during the 1800s were an omnipresent threat.

From the earliest days of the U.S. Post Office, workers performed the duties of today’s APWU members, sorting and distributing the mail, and getting it from station to station. The frequent attacks on couriers (including the riders of the short-lived Pony Express), stagecoaches, and railway cars that moved the mail across the expanding nation during the 1800s were an omnipresent threat.

Pony Express riders, for example, risked robberies, inhospitable desert and mountain roads, and bad weather, and often had to ride at night to keep the mail on schedule. Stagecoaches were ripe for holdup by gunmen who raided mail sacks for gold, bank certificates, and cash. (In 1881, outlaws attacked 86 stagecoaches.) Workers at the isolated way stations also could be imperiled — an important part of the job of the ranchhands, horseshoers, and coach-mechanics was to build and maintain friendships with the Native American population.

When the Railway Mail Service replaced stagecoaches, outlaws adjusted their tactics, including blowing up tracks to set up ambushes. The Old West celebrated by Hollywood was long over in 1921 when Postmaster General Will Hays complained to Congress that at least three dozen attacks on mail cars had netted thieves more than $6.3 million.

When the Railway Mail Service replaced stagecoaches, outlaws adjusted their tactics, including blowing up tracks to set up ambushes. The Old West celebrated by Hollywood was long over in 1921 when Postmaster General Will Hays complained to Congress that at least three dozen attacks on mail cars had netted thieves more than $6.3 million.

In addition to robberies, railway mail workers risked injury and even death from the frequent derailments and wrecks. For more than 50 years, the railway workplace was a rickety wooden car that could easily be crushed or catch fire in an accident. In one 10-year period, from 1890 to 1900, more than 80 clerks were killed and another 2,100 injured in train wrecks.

The pilots who pioneered the nation’s early Air Mail Service faced perhaps the greatest risks among those who moved the mail. Flying rudimentary aircraft without the benefit of modern weather forecasting and navigational aids, in the first nine years of the service (1918- 1927), 55 pilots died while flying the mail, and many others were injured in crashes.

Other postal workers went down with their crafts, most notably the three American clerks sorting mail on the Titanic in 1912. They were last seen trying to move 200 cumbersome mail sacks to higher decks.

The APWU is one of the sponsors of the Smithsonian exhibit, which opened on Oct. 8, 2003. You can see it online at www.postalmuseum.si.edu/duty/index.html.