‘Dust Bowl Troubadour’ Sang for Unions, Justice

April 30, 2013

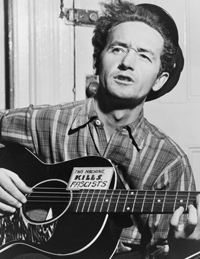

For more than a century, labor musicians have lifted spirits and helped build solidarity on union picket lines. But most Americans seldom heard labor’s voice — until one prolific entertainer helped popularize songs about the plight of everyday workers. Although he is mostly remembered as the man who wrote This Land Is Your Land, Woody Guthrie was a champion of workers, farmers and the unemployed.

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in 1912 to a relatively prosperous Oklahoma family that soon fell on hard times. His family’s home was destroyed by a fire, his sister died and his father was severely burned in subsequent fires, the family’s money disappeared when local oil and real estate booms ended, and his mother was sent to an insane asylum, where she later died.

By the 1920s, his father left to find work in Texas and Guthrie and one of his siblings were living largely on their own. “I was 13 when I went to live with a family of 13 people in a two-room house,” he recalled in his autobiography, Bound for Glory. To get by, he took on jobs “shining shoes, washing spittoons,” and carrying bags for guests at “a hotel uptown,” he recalled. Around that time, Guthrie began playing harmonica and guitar and first hit the road seeking odd jobs.

At 18, Guthrie re-united with his father in Pampa, a Texas panhandle town. Within a few years, on the eve of the Great Depression, the young man had married, started a family, and began to flourish as a singer-songwriter.

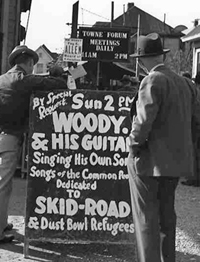

He and his band-mates played for rodeos, carnivals, and fairs, but things fell apart when catastrophic dust storms struck the Great Plains in 1935. Tens of thousands of desperate farmers and unemployed workers from the region fled west seeking work. Many went to California, where their dreams of making a living were often dashed by large farm-owners who sought to exploit the “Okies” and other new migrants to the state.

California

In 1937, Guthrie left his family behind, hitchhiking between migrant workers’ camps out West. Witnessing the plight of so many displaced and exploited working families, Guthrie came to believe that only a strong union movement could achieve social justice. Wherever there were farmworkers or union audiences, “He was the first one to show up and have his guitar to help lead a strike,” noted Elizabeth Partridge, a Guthrie biographer.

In 1938, Guthrie landed a job at a Los Angeles radio station singing traditional songs and some of his own compositions. The show also provided him with a forum to broadcast his progressive views on a wide array of union and political topics.

Guthrie identified with the thousands of displaced workers who listened to his program while living in makeshift shelters in migrant camps. He told their stories in songs like I Ain’t Got No Home, Goin’ Down the Road Feelin’ Bad, Talking Dust Bowl Blues, Tom Joad and Hard Travelin.

“It was clear to Woody that the people needed a voice to speak for them,” wrote Bonnie Christensen, another biographer. “They needed someone who was not afraid of the bosses, someone who knew what it was like to be poor.”

New York

In 1939, the restless young man left L.A. for New York City, where he performed on a CBS radio program, “Folk School on the Air.” He was recruited by folklorist Alan Lomax to record songs and stories for the Library of Congress, and he recorded Dust Bowl Ballads for RCA Victor.

Guthrie immersed himself in New York City’s folk music scene and began to win national acclaim as the “Poet of the People.” He and a loosely-knit group of musicians formed the Almanac Singers, which included Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Millard Lampell; blues greats Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and other notable performers. The band was committed to union organizing, defeating fascism, and promoting progressive political causes through song.

In 1941, the Almanac Singers recorded Talking Union, which included the timeless labor anthems, Which Side Are You On?, We Shall Not Be Moved and Solidarity Forever. The album also included two songs written by Guthrie: Roll the Union On and Union Maid, the ode to union women that includes the classic refrain, “Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union!”

On the Road Again

Becoming restless with the entertainment industry, Guthrie left New York to write songs about the Columbia River for the Bonneville Power Administration. Back in the West, he wrote several of his most famous songs celebrating the beauty of the land and the spirit of the American people, including Pastures of Plenty, Roll On Columbia and Grand Coulee Dam.

Guthrie had reunited his family, but his constant travel and a lack of steady income led to the end of his first marriage. He returned to New York, but was soon on the road for stints in the Merchant Marine and the U.S. Army during World War II.

After the war Guthrie married Marjorie Mazia, a modern dancer who shared his political ideals. They had four children and settled in Brooklyn, where he resumed his career and wrote a series of classic children’s songs.

Despite his success, the peace he had long sought continued to elude him as his second marriage dissolved and he began to show symptoms of Huntington’s disease, the neurological disorder that affl icted his mother.

Despite his success, the peace he had long sought continued to elude him as his second marriage dissolved and he began to show symptoms of Huntington’s disease, the neurological disorder that affl icted his mother.

Brushing aside the physical and emotional symptoms, in 1954 he hit the road again with his young protégé, folk musician Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Guthrie continued performing and composed songs inspired by the struggle for racial justice and concerns about the environment.

During the McCarthy Era in the early 1950s, Guthrie, Seeger and many of their associates were blacklisted from performing on TV and radio, and persecuted by the House Un-American Activities Committee for their progressive stances on the right to unionize, free speech, and equal rights. With his disease worsening, in late 1954 Guthrie began a lengthy series of hospitalizations in New York but he continued writing.

Legacy

In the early 1960s a new generation rejuvenated the progressive folk music that Guthrie had helped popularize. Bob Dylan and other rising folk singers often visited Guthrie in the hospital— with their guitars in hand — seeking his wisdom. Guthrie’s songs “had the infinite sweep of humanity in them,” Dylan said.

Woody Guthrie died on Oct. 3, 1967, at Creedmoor State Hospital in Queens, New York. A month later, his son, Arlo, released Alice’s Restaurant, which became an anthem of theRestaurant movement against the Vietnam War.

Woody Guthrie left behind more than 3,000 songs, several novels, and thousands of drawings, unpublished manuscripts, poems, prose, plays and hundreds of letters. Today his songs are performed by dozens of well-known artists who re-interpret them for pop, punk, country and rap audiences.

In 2012, a series of concerts celebrating the centennial of Guthrie’s birth featured Guthrie contemporaries Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and the ageless Pete Seeger; well-known artists such as Donovan, Jackson Browne, Graham Nash, Judy Collins, and Rosanne Cash; and a new generation of pro-union musicians like Ani Difranco and Tom Morello.

For more about Guthrie’s life and lyrics, visit www.woodyguthrie.org. His songs can be heard at www.folkways.si.edu