Labor Organizing Changed the Hawaiian Islands Forever

April 30, 2003

(This article was first published in the May/June 2003 issue of The American Postal Worker magazine.)

The birth of the Hawaiian labor movement was a painful experience, marked by a number of failed job actions on the islands’ sugar-cane plantations over the course of 50 years. The largely Asian workforce learned bitter lessons from several failed farm-worker strikes, most notably in 1909, 1920, and 1924, before the great strike of 1946. That all-island work stoppage was a success because workers of all races finally organized into a single labor union. Once it took root, labor organizing forever changed the Hawaiian islands, economically, politically and socially.

The Plantation System

Europeans arrived in Hawaii in 1778 and the first sugarcane plantation was established about 50 years later. By the middle of the 19th century, growers had to import workers to meet production demands.

In 1851, a group of growers formed the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society in part to address the “labor problem.” The growers pooled their resources to handle an expected influx of immigrants and instituted a contract-labor system: Plantation employees committed to working a fixed number of years, during which they were paid only subsistence wages.

Shortly after the growers’ association was formed, the first imported laborers arrived, from China. Before the end of the century, 46,000 Chinese workers had come to Hawaii.

Plantation work consisted of 10-hour days, six–day weeks. Women, paid two-thirds of what men were paid, weeded the fields, stripped the cane of dry leaves, or cut seed cane. Men handled the heavy work: Cutting, carrying, and loading raw sugar cane.

Ethnic Fragmentation

Whenever a group of workers at a sugar plantation grumbled about pay and conditions, they were threatened with replacement. The importation of non-Chinese workers began in the 1880s, with arrivals from Russia, Germany, Portugal, and Norway. And from 1886 to 1925, the sugar planters brought in 180,000 Japanese workers.

After Hawaii became a U.S. Territory in 1900, contract labor was declared illegal. But the growers had built up a large pool of workers. To sow disunity, plantation owners paid different nationalities at different wage rates. Distrust among the groups, each living in segregated plantation camps, was widespread.

The largest group was the first to organize. In 1909, about 5,000 Japanese workers — roughly 70 percent of the plantation employees — went on strike. Growers quickly hired Chinese, Hawaiian, Korean, and Portuguese strike-breakers at $1.50 a day, more than twice the going rate.

The strike was broken after three months, with the growers shortly thereafter raising wages and abolishing wage differentials based on race. They continued, however, to fragment the workforce, turning to Puerto Rico, Spain, and especially the Philippines for new labor.

The 1920 Strike

The next incident of widespread worker unrest had its roots in World War I-induced inflation. In 1917, the Young Men’s Association of Hawaii, an organization of Japanese Buddhists, held meetings on the issues of the cost of living and the wage scale. In Hilo, in late 1919, this organization of young men (most of them born in Hawaii) issued demands for an increase in pay. Over the course of several weeks, there were strikes on sugar plantations on all four of Hawaii’s major islands.

While the striking workers had some impact on production and profits, the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association won all the public relations battles. In this they were helped by the islands’ main newspapers, especially the Honolulu Advertiser, which hysterically denounced the strike as “a plot by Japan to take over Hawaii.”

As an institution, the growers association was strengthened by the strike. It even initiated a primitive social welfare program that alleviated some of the worst features of plantation life. In that sense at least, the 1920 strike succeeded.

The 1924 Strike

In 1924, about 13,000 Filipino workers struck the sugarcane industry. During eight months of what ultimately was a futile job action, 16 strikers and four police officers died in picket-line violence.

When the Territory of Hawaii found itself strapped for funds during prosecution of strikers, the HSPA contributed money to conduct the court cases. Not surprisingly, 60 of the 76 strikers put on trial received prison terms, most for four years, for their activities during picketing.

The main outcome of the 1924 strike was that it prompted the planters association to take its cause to Washington, where it lobbied to ease legislative restrictions on immigration. The growers were uneasy about the budding alliance of Japanese and Filipino workers and they hoped to be able to bring in more workers from a variety of countries.

The 1946 Strike

The job action of 1946 started with a premise that workers had to unite to succeed. Finally, workers recognized that only an organized force could face up to the growers. Finally, they recognized that everyone would have to take part.

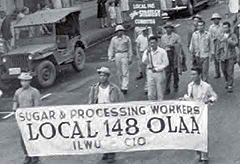

For the first time, labor leaders, largely from the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), were able to bring all races into a single Hawaiian labor union. Learning from the planters association, the first thing the workers did was set up a communications network. They knew it was necessary to reach across every language barrier if a multi-ethnic union were to succeed.

In 1946, more than 100,000 people, one-fifth of the population, lived and worked on the plantations, which controlled nearly every major economic activity in Hawaii. The ILWU is credited with uniting the different ethnic groups and keeping everyone informed and involved through an organizing effort that reached into every plantation, every camp, and every gang.

The 1946 strike began on Aug. 31, lasted 79 days, and was the first to shut down the industry. All but one of the 34 biggest plantations were struck, with more than 20,000 workers refusing to report to their jobs.

Community organizing was the strike’s lifeblood — soup kitchens were established, morale committees held talent nights and dances, community gardens were planted, “bumming committees” solicited stores for contributions to needy strikers, and activists recruited new members at ball fields and fishing haunts. The union became the bedrock of a new political order.

“The history of the 1946 sugar strike is the history of community organizing,” notes the University of Hawaii’s Center for Labor Education and Research. The strike’s success was “built upon the support of not just workers, but workers’ families, including children, themselves only a few years from working for the plantations. The legacy of the 1946 sugar strike is larger than sugar. Its legacy is the formation of a multi-ethnic community force working together to address social and political problems. Community organizing not only won the 1946 sugar strike, it also laid the foundation for political change.”