Eleanor Roosevelt: ‘One of Us’

February 28, 2013

Although she belonged to a prominent New York family and could have chosen a life of leisure, Eleanor Roosevelt was a tireless advocate for social and economic justice.

Much has been written about the nation’s longest serving and most outspoken first lady, who helped launch the modern civil rights and women’s movements. But the enormous impact she had on the union movement is often overlooked, notes Brigid O’Farrell, author of She Was One of Us: Eleanor Roosevelt and the American Worker.

“Mrs. Roosevelt believed that everyone deserved the right to a decent job, a living wage, safe working conditions and a voice at work,” O’Farrell said. “Her compelling vision of labor rights as human rights was widely known during her lifetime but has been marginalized or forgotten since her death.”

The only first lady ever to carry a union card was a member of the Newspaper Guild, which she joined when she began writing the My Daycolumn in 1937. Her articles appeared in hundreds of newspapers across the country for the next 25 years. ER, as she often signed her name, used her columns, speeches and behind-the-scenes advocacy to advance the union cause.

Early Life

Born in 1884, ER was concerned about the lives of the less fortunate as a young woman. Both of her parents and one of her two brothers died before she turned 10. She was soon sent to a boarding school in London, where she was deeply influenced by a progressive headmistress.

At 17, the debutante niece of then-president Theodore Roosevelt returned to New York City. Instead of frolicking with the elite, she volunteered at a “settlement house” that provided social services to needy women and children living in East Side tenements. After learning first-hand about the hardships they faced, she joined the National Consumers League, which sought to protect women and children from exploitation by employers.

At 17, the debutante niece of then-president Theodore Roosevelt returned to New York City. Instead of frolicking with the elite, she volunteered at a “settlement house” that provided social services to needy women and children living in East Side tenements. After learning first-hand about the hardships they faced, she joined the National Consumers League, which sought to protect women and children from exploitation by employers.

In 1905, she married and started a family with Franklin D. Roosevelt, a fifth-cousin and an aspiring politician. While FDR served as Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy in Washington, ER volunteered for the Women’s Trade Union League and met many labor activists who would become lifelong friends.

The young mother stepped up her political involvement after FDR contracted polio in 1921. While he recuperated, she often appeared on his behalf at events held by unions and women’s groups.

But ER was not content to give speeches. She was an activist. She walked union picket lines with garment workers; lobbied the New York legislature for a shorter work week and against child labor; fought to include the right to join a union in the 1924 Democratic Party platform, and campaigned to elect Robert Wagner to the U.S. Senate. When FDR was elected governor of New York in 1928, ER helped Frances Perkins become the state’s commissioner of labor. Wagner and Perkins became key architects of the New Deal labor reforms FDR instituted after he became president in 1933.

First Lady

As America’s first lady during the Great Depression, ER acted as FDR’s “eyes and ears,” touring the nation’s soup kitchens, farms, and industrial centers. After visiting a West Virginia mining town in 1933, “Mrs. Roosevelt regularly denounced dangerous working conditions and opposed feudal company policies that drove miners into debt and forced them to patronize company stores,” O’Farrell wrote.

Though she publicly downplayed her influence in her husband’s administration, she was said to be a persuasive behind-the-scenes advocate for citizens who were out of work or exploited by unscrupulous employers. “No one who ever saw Eleanor Roosevelt sit down facing her husband and, holding his eye firmly, say to him, ‘Franklin, I think you should ...’ or, ‘Franklin, surely you will not ...’ will ever forget the experience,” recalled Rexford Tugwell, a close aide to the president.

ER once said, “There are only two ways to bring about protection for workers... legislation and unionization.” Working with Wagner and Perkins, she helped make both happen.

ER used her speeches, interviews, and columns to build support for the landmark National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which guaranteed workers the right to join unions and bargain collectively for improved wages, benefits and working conditions. She also supported the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which outlawed child labor, and established a minimum wage, the 40-hour workweek, and overtime pay. In the decades that followed, the union movement blossomed and the middle class grew. Workers earned a better living, and were able to own homes and send their kids to college.

After the White House

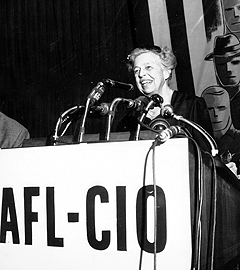

Following FDR’s death in April 1945, ER continued speaking out for workers’ rights and human rights at home and abroad. She authored 16 books, wrote hundreds of articles,  frequently appeared on radio and TV, and spoke at many union conventions.

frequently appeared on radio and TV, and spoke at many union conventions.

And unlike any former first lady before her, she remained active in government and politics. As a member of the American delegation to the United Nations from 1946 to 1953, ER chaired the assembly’s permanent Commission on Human Rights.

At the UN, she shaped and helped win approval for its historic Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states, “Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions,” has a right to “equal pay for equal work,” and “an existence worthy of human dignity.” When asked, “Where, after all, do human rights begin?” Eleanor Roosevelt answered, “In small places close to home… the neighborhood…the school…the factory, farm or office…unless they have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”

In the 1950s, ER fought to protect the rights U.S. workers had gained during the New Deal. An anti-labor Congress had passed the Taft-Harley Act, which allowed states to undermine the NLRA through “right-to-work” laws.

ER co-chaired a national effort to defeat the anti-union measures and called for “all right-thinking citizens, from all walks of life, to join in protecting the nation’s economy and the working man’s union security from the predatory and misleading campaigns now being waged by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers.” Right-to-work legislation, she said, “does nothing for working people, but instead gives employers the right to exploit labor.”

ER co-chaired a national effort to defeat the anti-union measures and called for “all right-thinking citizens, from all walks of life, to join in protecting the nation’s economy and the working man’s union security from the predatory and misleading campaigns now being waged by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers.” Right-to-work legislation, she said, “does nothing for working people, but instead gives employers the right to exploit labor.”

Near the end of her life, ER headed the U.S. Commission on the Status of Women, formed by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, and fought for passage of the 1963 Equal Pay Act, to reduce the pay disparity between men and women.

When she died at age 78 in 1962, she still had her union card in her wallet.

“Throughout the crowded years of her lifetime, Eleanor Roosevelt was the tireless champion of working men and women,” says an AFL-CIO tribute. “She was on our side, fighting for our right to organize… standing shoulder to shoulder with the rest of us in labor’s ranks… but more that: She was one of us.”